Cordillera Paine

Cordillera Paine

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| Cordillera Paine | |

|---|---|

Torres del Paine, Chile | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Cerro Paine Grande |

| Elevation | 2,884 m (9,462 ft) |

| Coordinates | 50°59′56″S 73°05′43″W / 50.99889°S 73.09528°W / -50.99889; -73.09528 |

| Geography | |

NASA image with annotations | |

| Country | Chile |

| State/Province | Magallanes y Antártica Chilena |

| Range coordinates | 51°S 73°W / 51°S 73°W / -51; -73Coordinates: 51°S 73°W / 51°S 73°W / -51; -73 |

| Parent range | Patagonian Andes |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 12 Myr |

| Type of rock | Granite |

The Cordillera Paine is a small mountain group in Torres del Paine National Park in Chilean Patagonia. It is located 280 km (170 mi) north of Punta Arenas, and about 1,960 km south of the Chilean capital Santiago. It belongs to the Commune of Torres del Paine in Última Esperanza Province of Magallanes and Antártica Chilena Region. No accurate surveys have been published, and published elevations have been claimed to be seriously inflated, so most of the elevations given on this page are approximate.[1]Paine means "blue" in the native Tehuelche (Aonikenk) language and is pronounced PIE-nay.[2]

Contents

1 Peaks

2 Geology

3 Hiking

4 See also

5 References

6 External links

Peaks[edit]

The highest summit of the range is Cerro Paine Grande, at 50°59′56″S 73°05′43″W / 50.99889°S 73.09528°W / -50.99889; -73.09528. For a long time its elevation was claimed to be 3,050 m or 3,251 m, but in August 2011 it was ascended for the third time, measured using GPS and found to be 2,884 m.[3]

The best-known and most spectacular summits are the three Towers of Paine (Spanish: Torres del Paine, 50°57′09″S 72°59′23″W / 50.95250°S 72.98972°W / -50.95250; -72.98972).

The South Tower of Paine (about 2,500 m,[1] at 50°57′33″S 72°59′42″W / 50.95917°S 72.99500°W / -50.95917; -72.99500) is now thought to be the highest of the three, although this has not been definitely established. It was first climbed by Armando Aste.

The Central Tower of Paine (about 2,460 m or 8,100 feet[1]) was first climbed in 1963 by Chris Bonington and Don Whillans, and the North Tower of Paine (about 2,260 m) was first climbed by Guido Monzino.

Other summits include the Cuerno Principal, about 2,100 m,[1] and Cerro Paine Chico, which is usually correctly quoted at about 2,650 m.[1]

Geology[edit]

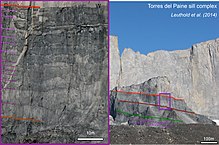

Torres del Paine mafic sill complex built up by successive magma injections

The range is made up of a yellowish granite underlain by grey gabbro-diorite laccolith and the sedimentary rocks it intrudes, deeply eroded by glaciers. The steep, light colored faces are eroded from the tougher, vertically jointed granitic rocks, while the foothills and dark cap rocks are the sedimentary country rock, in this case flysch deposited in the Cretaceous and later folded.[4]

The radiometric age for the quartz diorite at Cerro Paine is 12 ± 2 million years by the rubidium-strontium method and 13 ± 1 million years by the potassium-argon method.[5] More precise ages of 12.59 ± 0.02 and 12.50 ± 0.02 million years for the earliest and latest identified phases of the intrusion, respectively, were achieved using Uranium–lead dating methods on single zircon crystals.[6] Basal gabbro and diorite were dated by a similar technique to 12.472 ± 0.009 to 12.431 ± 0.006 million years.[7] Thus, magma was intruded and crystallized over 162 ± 11 thousand years. High resolution dating and excellent 3-D exposure of the laccolith and its vertical feeding system allow detailed reconstruction of the Torres del Paine fossil magma chamber history.[8]

Hiking[edit]

Lago Pehoé

The Torres del Paine National Park—an area of 2,400 km²—was declared a Biosphere Reserve by the UNESCO in 1978 and is a popular hiking destination. There are clearly marked and well maintained paths and many refugios which provide shelter and basic services.

Hikers can opt for a day trip to see the towers, walk the popular "W" route in about five days, or trek the full circle in 8–9 days.

The "W" route is by far the most popular, and is named for the shape of the route. Hikers start and finish at either of the base points of the "W", performing each of the three shoots as a day trip. The five points of the W, from west to east, are:

Glacier Grey, a large glacier calving into the lake of the same name. Camping is available next to Refugio Grey.- Refugio Paine Grande, situated on Lago Pehoé. This site offers good views of the "horns" of Torres del Paine.

- Valle del Francés ("Frenchman's Valley"), often rated as the best scenery in the whole park. The path leads up into a snowy dead-end, where several small glaciers are visible.

- Hotel Las Torres, a large hotel at the base of the mountain range.

- The Torres del Paine themselves, large rock formations over a small lake, high in the mountains.

The longer "circuit" walk includes all the sights of the "W", but avoids most backtracking, by connecting Glacier Grey and the Torres del Paine around the back of the mountain range.

Boats and buses provide transport between Hotel Las Torres, Refugio Paine Grande, and the park entrance at Laguna Amarga.

It is a national park and thus hikers are not allowed to stray from the paths. Camping is only allowed at specified campsites, and wood fires are prohibited in the whole park.

The Paine "horns," with the typical extreme weather of the region

See also[edit]

- Fitz Roy

- Los Glaciares National Park

References[edit]

^ abcde Biggar, John, 2015. The Andes: A Guide for Climbers (4th edition, ISBN 978-0-9536087-4-4). Several elevations given by this authority are much lower than those given by other authorities, and the higher elevations are not supported by official Chilean IGM maps.

^ Abraham, Rudolf (2011). Torres del Paine: Trekking in Chile's Premier National Park. Milnthorpe: Cicerone Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-84965-356-5. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

^ 2011 Expedition

^ Altenberger, Uwe; Oberhänsli, Roland; Putlitz, Benita; Wemmer, Klaus (1 July 2003). "Tectonic controls and Cenozoic magmatism at the Torres del Paine, southern Andes (Chile, 51°10'S)". Revista geológica de Chile. 30 (1): 65–81. doi:10.4067/S0716-02082003000100005 – via SciELO.

^ Martin Halpern "Regional Geochronology of Chile South of 50 degrees Latitude", Bulletin Geological Society of America, v. 84, p. 2410, 1973.

^ Juergen Michel, Lukas Baumgartner, Benita Putlitz, Urs Schaltegger and Maria Ovtcharova, Incremental growth of the Patagonian Torres del Paine Laccolith over 90 k.y., Geology, 36(6):459-462, 2008.

^ Julien Leuthold, Othmar Müntener, Lukas Baumgartner, Benita Putlitz, Maria Ovtcharova and Urs Schaltegger, Time resolved construction of a bimodal laccolith (Torres del Paine, Patagonia), Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 325-326:85-92, 2012.

^ Julien Leuthold, Othmar Müntener, Lukas Baumgartner, Benita Putlitz, Petrological constraints on the recycling of mafic crystal mushes and intrusion of braided sills in the Torres del Paine Mafic Complex (Patagonia), Journal of Petrology, 55(5):917-949, 2014.

- Biggar, John, 2015. The Andes: A Guide for Climbers (4th edition, ISBN 978-0-9536087-4-4).

- Kearney, Alan, 1993. Mountaineering in Patagonia. Seattle USA: Cloudcap.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cordillera del Paine. |

- Complete description of Torres del Paine in Andeshandbook

- x666AFSFASDDFFA Patagonia Webcam and maps from Paine

- Torres del Paine on summitpost

- Torres del Paine Circuit Planning

- Photograph of the cordillera from Estero Última Esperanza, 50 km to the south

Categories:

- Mountain ranges of Chile

- Última Esperanza Province

- Landforms of Magallanes y la Antártica Chilena Region

- Miocene magmatism

- Torres del Paine National Park

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function()mw.config.set("wgPageParseReport":"limitreport":"cputime":"0.368","walltime":"0.447","ppvisitednodes":"value":2791,"limit":1000000,"ppgeneratednodes":"value":0,"limit":1500000,"postexpandincludesize":"value":43967,"limit":2097152,"templateargumentsize":"value":10985,"limit":2097152,"expansiondepth":"value":16,"limit":40,"expensivefunctioncount":"value":0,"limit":500,"unstrip-depth":"value":0,"limit":20,"unstrip-size":"value":5775,"limit":5000000,"entityaccesscount":"value":1,"limit":400,"timingprofile":["100.00% 378.220 1 -total"," 55.35% 209.354 1 Template:Infobox_mountain_range"," 44.52% 168.402 1 Template:Infobox"," 23.03% 87.099 1 Template:Reflist"," 16.28% 61.561 4 Template:Convert"," 11.00% 41.595 3 Template:ISBN"," 10.39% 39.301 1 Template:About"," 9.97% 37.704 1 Template:Cite_journal"," 8.93% 33.792 1 Template:Convinfobox"," 8.33% 31.509 1 Template:Convinfobox/pri2"],"scribunto":"limitreport-timeusage":"value":"0.155","limit":"10.000","limitreport-memusage":"value":5937123,"limit":52428800,"cachereport":"origin":"mw2181","timestamp":"20180918134624","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false);mw.config.set("wgBackendResponseTime":80,"wgHostname":"mw2182"););

Clash Royale CLAN TAG

Clash Royale CLAN TAG