Mozambican Civil War

Mozambican Civil War

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

| Mozambican Civil War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Cold War | |||||||

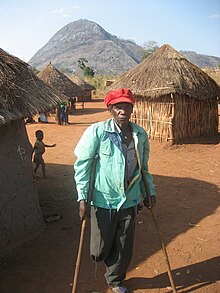

Victim of land mines set up during the war. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

FRM (merged with RENAMO in 1982)[2] | |||||||

Supported by:

| Supported by:

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

~20,000[8] | |||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

Unknown | |||||||

Total killed: ~1,000,000 (including from famine) | |||||||

The Mozambican Civil War was a civil war fought in Mozambique from 1977 to 1992. Like many regional African conflicts during the late twentieth century, the Mozambican Civil War possessed local dynamics but was also exacerbated greatly by the polarizing effects of Cold War politics.[4] The war was fought between Mozambique's ruling Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO) and insurgent forces of the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO).[11]

RENAMO opposed FRELIMO's attempts to consolidate its rule under a socialist one-party state, and was backed by anti-communist governments in Rhodesia and South Africa.[4] For their part, the Rhodesian and South African defence establishments used RENAMO as a proxy to erode FRELIMO support for militant nationalist organisations in their own countries.[4] About one million Mozambicans were killed in the fighting or starved due to interrupted food supplies; an additional five million were displaced.[12][13] The Mozambican Civil War destroyed much of Mozambique's rural infrastructure, including hospitals, rail lines, roads, and schools.[11] FRELIMO's security forces and RENAMO insurgents were accused of committing numerous human rights abuses, including using child soldiers and salting a significant percentage of the countryside indiscriminately with land mines.[11] Three neighboring states—Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and Malawi—eventually deployed troops into Mozambique to defend their own vested economic interests against RENAMO attacks.[11]

The Mozambican Civil War ended in 1992, following the collapse of Soviet and South African support for FRELIMO and RENAMO, respectively.[4] Direct peace talks began around 1990 with the mediation of the Mozambican Church Council and the Italian government; these culminated in the Rome General Peace Accords which formally ended hostilities.[11] As a result of the Rome General Peace Accords, RENAMO units were demobilized or integrated into the Mozambican armed forces and the United Nations Operation in Mozambique (ONUMOZ) was formed to aid in postwar reconstruction.[11] Tensions between RENAMO and FRELIMO flared again between 2013 and 2018, prompting the former to resume its insurgency.[14][15]

Contents

1 Background

1.1 Independence

1.2 Geo-political situation

1.3 Internal Mozambican tensions

1.3.1 FRELIMO dissidents

1.3.2 Overturning of traditional hierarchies and re-education camps

2 Course of the war

2.1 Outbreak

2.2 RENAMO strategies and operations

2.3 FRELIMO strategies and operations

2.4 Foreign support and intervention

2.5 Military stalemate

3 War crimes and crimes against humanity

3.1 RENAMO

3.2 FRELIMO

4 Aftermath

4.1 Transition to peace

4.2 Landmines

4.3 Resurgence of violence since 2013

5 References

6 Bibliography

7 External links

Background[edit]

Independence[edit]

Portugal fought a long and bitter counter-insurgency conflict in its three primary African colonies—Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau—from the 1960s to the mid-1970s, when they finally received independence following the Carnation Revolution. In Mozambique, the armed struggle against colonial rule was spearheaded by the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), which was initially formed in exile[16] but later succeeded in wresting control of large sections of the country from the Portuguese.[17] FRELIMO drew its popular base of support primarily from Mozambican migrant workers and expatriate intellectuals who had been exposed to the emerging popularity of anti-colonial and nationalist causes overseas, as well as the Makonde and other ethnic groups in northern Mozambique, where Portuguese influence was weakest.[16][18] The bulk of its members were drawn from Makonde workers who had witnessed pro-independence rallies in British-ruled Tanganyika.[16] In September 1964, FRELIMO commenced an insurgency against the Portuguese.[16] Its decision to take up arms was influenced by a number of factors, namely the recent successes of indigenous anti-colonial guerrilla movements in French Indochina and French Algeria, as well as encouragement from contemporary African statesmen such as Ahmed Ben Bella, Gamal Abdel Nasser, and Julius Nyerere.[16] FRELIMO guerrillas received training primarily in North Africa and the Middle East, with the Soviet Union and People's Republic of China providing military equipment.[16]

Portugal responded by embarking on a massive buildup of military personnel and security forces in Mozambique.[16] It also established close defence ties with two of Mozambique's neighbours, Rhodesia and South Africa.[16] In 1970, the Portuguese launched Operation Gordian Knot, which was successful at eliminating large numbers of FRELIMO guerrillas and their support bases; however, the redeployment of so many Portuguese troops to northern Mozambique allowed FRELIMO to intensify its operations elsewhere in the country.[19] The following year, Portugal established an informal military alliance with Rhodesia and South Africa known as the Alcora Exercise.[19] Representatives from the defence establishments of the three countries agreed to meet periodically to share intelligence and coordinate operations against militant nationalist movements in their respective countries.[19] Simultaneously, FRELIMO also pursued close relations with the latter; for example, by 1971 it had cultivated an alliance with the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA).[19] ZANLA insurgents were permitted to infiltrate Rhodesia from FRELIMO-held territory.[19]

On 25 April 1974 the authoritarian regime of Estado Novo had been overthrown in Lisbon, a move that was supported by many Portuguese workers and peasants. The Armed Forces Movement (Movimento das Forças Armadas) in Portugal pledged a return to civil liberties and an end to the fighting in all colonies (or the "overseas provinces"). The rapid chain of events within Portugal caught FRELIMO, which had anticipated a protracted guerrilla campaign, by surprise. It responded quickly to the new situation, and on 7 September 1974 won an agreement from the Armed Forces Movement to transfer power to FRELIMO within a year. When this was made known to the public, several thousand Portuguese colonials fled the newly independent country. As a result of the exodus, the economy and social organization of Mozambique collapsed. On 25 June 1975 Mozambique gained independence from Portugal, with Samora Machel as the Head of State.

Geo-political situation[edit]

The geopolitical situation of Rhodesia in 1965. Rhodesia is coloured green and countries friendly to the government (South Africa and Portugal) are shown in purple.

The geopolitical situation of Rhodesia after the independence of Angola and Mozambique in 1975. Rhodesia itself is shown in green, nations friendly to the nationalist guerrillas are shown in orange, and South Africa and its dependency South-West Africa (now Namibia) are coloured purple.

The independence of Mozambique and Angola in 1975 challenged white minority rule in southern Africa. First, the independence wars in Angola and Mozambique demonstrated that even with great military resources it was virtually impossible for a small white minority to guarantee the safety of its members, let alone to exert control over a hostile black population outside of major power centres. The downfall of Portuguese rule gave hope to black resistance in South Africa and Rhodesia. Second, in both countries revolutionary socialist movements gained power. These movements had been cooperating with the black resistance movements in South Africa and Rhodesia, and now openly supported them, as well as offering them a safe haven from where they could coordinate their operations and train new forces. As President Machel put it in a speech in 1975: "The struggle in Zimbabwe is our struggle".[20]

This was especially devastating for white-ruled Rhodesia, whose armed forces lacked the manpower to effectively protect its 800-mile border with Mozambique against entering insurgents. At the same time, the apartheid government and the Smith regime lost Portugal as an ally and with it the tens of thousands of soldiers that had been deployed in the Portuguese colonial wars. Thus South Africa's and Rhodesia's white minorities' position were severely weakened by the events of 1974/75. Subsequently, undermining the newly independent countries' capacity to support their neighboring brothers in arms became South Africa's and Rhodesia's main strategy to counter this new threat. This manifested itself in the Rhodesia-sponsored foundation of RENAMO in 1975 and in South Africa's adoption of the "Total National Strategy".

Internal Mozambican tensions[edit]

FRELIMO dissidents[edit]

Soon after independence, FRELIMO announced Mozambique's transformation into a socialist one-party-state. This was accompanied by crackdowns on dissidents and the nationalization of important branches.[20] The leaders of the PCN, a new party in favour of multi-party-governance founded by prominent FRELIMO dissidents, were arrested and convicted in show trials. They were later extrajudicially executed.

Furthermore, nationalization of many Portuguese-owned enterprises, fear of retaliation among Whites, and an ultimatum to either choose Mozambican citizenship or leave the country within 90 days, drove the majority of the 370,000 White Portuguese Mozambicans out of the country. This resulted in economic collapse and chaos, as only few Africans had received higher education or even primary education under Portuguese rule.[20]

Overturning of traditional hierarchies and re-education camps[edit]

As a revolutionary Marxist party, FRELIMO embarked on overturning traditional governance structures in order to gain full control over every aspect of society. Therefore, local chiefs were ousted and thousands of dissidents were imprisoned in so called re-education camps.[21] Another source of conflict was the continuation of the aldeamento system that the Portuguese had introduced as a means of exerting control and inhibiting contact between the population and the rebels. It forced the rural populace to move into central communal villages, the aldeamentos. FRELIMO hoped that this system would enable the fulfillment of its agricultural development goals, but its implementation alienated the rural population. This was especially the case in central and northern Mozambique, where households are traditionally separated by considerable distances.[22]

Course of the war[edit]

Outbreak[edit]

From 1976 to 1977, Rhodesian troops repeatedly entered Mozambique in order to carry out operations against ZANLA (Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army) bases tolerated on Mozambican territory by the FRELIMO government.[23] During one such raid, Rhodesian forces freed FRELIMO ex-official André Matsangaissa from a reeducation camp. He was given military training and installed as leader of RENAMO, which had been founded by the Rhodesian secret service shortly before. It was created in Salisbury, Rhodesia under the auspices of Ken Flower, head of the Rhodesian CIO, and Orlando Christina, an ex Portuguese Secret Police operative with long experience in Africa.[8] RENAMO subsequently started operating in the Gorongosa area in order to fight FRELIMO and ZANLA. However, in 1979 Matsangaissa died in RENAMO's unsuccessful first attack on a regional centre (Villa Paiva) and RENAMO was ousted from the area. Subsequently, Afonso Dhlakama became the new leader of RENAMO and formed it into an effective guerilla army.[24]

RENAMO strategies and operations[edit]

Having fought the Portuguese using guerrilla strategies, FRELIMO was now forced to defend itself against the very same methods. It had to defend vast areas and hundreds of locations, while RENAMO operated out of a few remote areas, carrying out raids against towns and important infrastructure. Furthermore, RENAMO systematically forced civilians into its employment. This was done by mass abduction, especially of children in order to use them as soldiers. It is estimated that one third of RENAMO forces were child soldiers.[25] But abducted people also had to serve RENAMO in administrative or public service functions in the areas it controlled. Another way of using civilians for military purposes was the so-called system of "Gandira". This system especially affected the rural population in areas controlled by RENAMO, forcing them to fulfill three main tasks: 1) produce food for RENAMO, 2) transport goods and ammunition, 3) in the case of women, serve as sex slaves.[26]

Both sides heavily relied on the use of land mines; FRELIMO as a means to defend important infrastructure, RENAMO in order to terrify the populace, stall the economy and destroy the civil services, mining roads, schools and health centres.

Thus, despite its far superior numbers, FRELIMO was unable to adequately defend any but the most important cities. By the mid-1980s, FRELIMO had lost control of much of the countryside. RENAMO was able to carry out raids virtually anywhere in the country except for the major cities. Transportation had become a perilous business. Even armed convoys were not safe from RENAMO attacks.[27]

FRELIMO strategies and operations[edit]

FRELIMO reacted by reusing a system first introduced by the Portuguese: the creation of fortified communal villages called aldeamentos where much of the rural population was relocated. Furthermore, in order to keep a minimum level of infrastructure working, three heavily guarded and mined corridors were established consisting of roads, railways and power lines: the Beira, the Tete (also called the Tete Run which speaks for itself regarding its safety) and the Limpopo Corridors.[28]

Foreign support and intervention[edit]

FRELIMO initially received substantial military and development aid from the Soviet Union and later additionally from France, the UK and the U.S. In the U.S., conservative circles lobbied for the support of RENAMO but were opposed by the State Department, which finally gained the upper hand following reports which documented RENAMO's brutality. RENAMO received military support from Rhodesia, South Africa, and Kenya as well as organisational support from West Germany.[8]

In 1982, landlocked Zimbabwe directly intervened in the civil war in order to secure its transport ways, stop cross-border RENAMO raids, and help its old ally FRELIMO. Zimbabwe's help was crucial to the defense of the corridors. Later Zimbabwe became engaged further, carrying out several joint operations with FRELIMO against RENAMO strongholds.[28] Thus RENAMO had to give up its base camps in the Gorongosa area. Tanzania also sent troops to back FRELIMO. North Korea also armed and trained FRELIMO forces through a military mission it established in Mozambique during the early 1980s.[3] North Korean advisers were instrumental in the formation of FRELIMO's first specialized counter-insurgency brigade, which was deployed from 1983 onward.[3]

Malawi had a complicated relationship with both FRELIMO and RENAMO.[1] During the mid-1980s, FRELIMO repeatedly accused Malawian president Hastings Banda of providing sanctuary for RENAMO insurgents.[1] Mozambican security forces occasionally carried out raids into Malawi to strike at suspected RENAMO base camps in that country, a practice which brought them into direct confrontation with the Malawian Defence Force.[1] In 1986, Malawi bowed to Mozambican pressure and expelled 12,000 RENAMO insurgents.[1] Banda explicitly turned against RENAMO after the disgruntled insurgents began targeting a vital rail line which linked Blantyre to Mozambican ports on the Indian Ocean coast.[1] Beginning in April 1987 the Malawian government deployed troops into Mozambique to defend the rail line, where they were involved in a number of engagements with RENAMO.[1]

After 1980, South Africa became RENAMO's main supporter. The FRELIMO administration, led by President Machel, was economically ruined by the civil war. The military and diplomatic entente with the Soviet Union could not alleviate the nation's economic misery and famine. As a result, a reluctant Machel signed a non-aggression pact with South Africa, known as the Nkomati Accord. In return, Pretoria promised to sever economic assistance in exchange for FRELIMO's commitment to prevent the ANC from using Mozambique as a sanctuary to pursue its campaign to overthrow white minority rule in South Africa. Following a May 1983 car bombing in Pretoria, South African troops attacked suspected ANC bases in Maputo. In October, they raided the capital a second time, attacking an office building said to have been used by the organization. With the economy in shambles, Machel was forced to scale back some socialist policies; in a visit to Western Europe that same month, Machel agreed to military and economic pacts with Portugal, France, and the UK. He also abandoned the idea of collectivized agriculture, a result of which the Soviet Union terminated all aid to Mozambique. The volume of direct South African government support for RENAMO diminished after the Nkomati Accord, but documents discovered during the capture of RENAMO headquarters at Gorongosa in central Mozambique in August 1985 revealed continuing South African communications and military support for RENAMO. FRELIMO, meanwhile, only partially honored commitments to expel various ANC members from its territory.

Military stalemate[edit]

By the end of the 1980s neither side was able to win the war by military means. The military pressure on RENAMO had not resulted in its defeat. While being incapable of capturing any large cities, it was still able to terrorize the rural areas. FRELIMO controlled the urban areas and the corridors, but was unable to protect the countryside from RENAMO squadrons. FRELIMO was also unable to pin down RENAMO and force it into a direct full-scale confrontation.

On 19 October 1986, President Machel died when his presidential aircraft crashed near South Africa's border. An international investigation determined that the crash was caused by errors made by the flight crew, a conclusion that is not universally accepted. Machel's successor was Joaquim Alberto Chissano, who had served as foreign minister from 1975 until Machel's death. Chissano continued Machel's policies of expanding Mozambique's international ties, particularly the country's links with the West, and pursuing internal reforms.

During the war, hundreds of thousands of people died from famine.[29][30][31] The famine was attributable to both the policies of RENAMO and FRELIMO.[29][30]

War crimes and crimes against humanity[edit]

RENAMO[edit]

RENAMO systematically committed war crimes and crimes against humanity as part of its destabilization strategy. These include mass killing, rape and mutilation of non-combatants during terroristic raids on villages and towns, the use of child soldiers and the employment of the Gandira system, based upon forced labour and sexual violence. Often women would be apprehended while out in the fields, then raped as a means to boost troop morale. Gandira caused widespread starvation among the rural population due to the little time left to produce food for themselves. This caused more and more persons to be physically unable to endure the long transportation marches demanded from them. Refusing to participate in Gandira or falling behind on the marches resulted in severe beating and often execution.[32] Flight attempts were also punished harshly. One particularly gruesome practice was the mutilation and killing of children left behind by escaped parents.[33][34]

RENAMO crimes gained worldwide public attention when RENAMO soldiers butchered 424 civilians, including the patients of a hospital, with guns and machetes during a raid on the rural town of Homoine.[35] This incident prompted an investigation into RENAMO methods by US-State Department consultant Robert Gersony, which finally put an end to conservative ambitions for US-government support for RENAMO.[36] The report concluded that RENAMO's actions in Homoine did not significantly differ from the tactics it normally employed in such raids. These methods are described in the report in the following way:

The attack stage was sometimes reported to begin with what appeared to the inhabitants to be the indiscriminate firing of automatic weapons by a substantial force of attacking RENAMO combatants. […] Reportedly the Government soldiers aim their defensive fire at the attackers, while the RENAMO forces shoot indiscriminately into the village. In some cases refugees perceived that the attacking force had divided into three detachments: one conducts the military attack; another enters houses and removes valuables, mainly clothing, radios, food, pots and other possessions; a third moves through the looted houses with pieces of burning thatch setting fire to the houses in the village. There were several reports that schools and health clinics are typical targets for destruction. The destruction of the village as a viable entity appears to be the main objective of such attacks. This type of attack causes several types of civilian casualties. As is normal in guerrilla warfare, some civilians are killed in crossfire between the two opposing forces, although this tends in the view of the refugees to account for only a minority of the deaths. A larger number of civilians in these attacks and other contexts were reported to be victims of purposeful shooting deaths and executions, of axing, knifing, bayoneting, burning to death, forced drowning and asphyxiation, and other forms of murder where no meaningful resistance or defense is present. Eyewitness accounts indicate that when civilians are killed in these indiscriminate attacks, whether against defended or undefended villages, children, often together with mothers and elderly people, are also killed. Varying numbers of civilian victims in each attack were reported to be rounded up and abducted [...].[37]

Thus it appears the only difference between the Homoine massacre and RENAMO's usual methods was the size of the operation. Normally RENAMO would choose smaller, easier targets instead of attacking a town defended by some 90 government soldiers.[38]

According to the Gersony Report, RENAMO's transgressions were far more systematic, widespread and grave than FRELIMO's: the refugees interviewed for the Gersony Report attributed 94% of the murders, 94% of the abductions and 93% of the lootings to RENAMO.[39] However, this conclusion has been disputed by the French Marxist scholar Michel Cahen, who states that both sides were equally to blame:

There can be no doubt that the war was largely one fought against civilians... I am also convinced that the war was equally savage on both sides, even if the total domination of the media by FRELIMO for the 15 years of the war has led even those most desirous of remaining objective to attribute the majority of the atrocities to RENAMO. The people themselves were not duped: they attributed various acts of banditry and certain massacres to "RENAMO 1," but others to "RENAMO 2" – the euphemistic term for FRELIMO soldiers and militiamen acting on their own.[40]

Rudolph Rummel estimated the democide of the RENAMO rebels between 1975 and 1987 to be at least 125,000 killed.[41][better source needed]

FRELIMO[edit]

FRELIMO soldiers also committed serious war crimes during the civil war.[42] Much like RENAMO, FRELIMO forced people into its employment. Living in the communal villages was mandatory. However, in some areas cultural norms require households to live at some distance from each other. Therefore, many people preferred living in the countryside despite the risk of RENAMO assaults.[43] Thus people would often be forced into the communal villages at gunpoint by FAM-soldiers or their Zimbabwean allies. As a local recalls:

I never wanted to leave my old residence and come to the communal village. Even with the war, I wanted to stay where I had my land and granaries. Ever since a long time ago, we never lived with so many people together in the same place. Everyone must live in his own yard. The Komeredes [Zimbabwean soldiers] came to my house and said that I should leave my house and go to the communal village where there were a lot of people. I tried to refuse and then they set fire to my house, my granaries, and my fields. They threatened me with death and they told me and my family to go forward. Inside the communal village we lived like pigs. It was like a yard for pigs. We were so many people living close to each other. If someone slept with his wife everyone could listen to what they were doing. When we went to the fields or to the cemeteries to bury the dead, the soldiers had to come behind and in front of us. When the women went to the river to wash themselves, the soldiers had to go too and they usually saw our women naked. Everything was a complete shame inside that corral. Usually to eat, we had to depend on humanitarian aid, but we never knew when it would arrive. It was terrible; that is why many people used to run away from the communal village to their old residences where RENAMO soldiers were, although it was also terrible there.[43]

Rape was also a widespread practice among FRELIMO soldiers. However, it was far less frequent and lacked the institutionalised quality of sexual violence carried out by RENAMO.[44]

Despite the massive scale and organized manner in which war crimes and crimes against humanity had been committed during the Mozambican civil war, so far not one RENAMO or FRELIMO commander has appeared before a war crimes tribunal of any sort. This is due to the unconditional general amnesty law for the period from 1976-1992 passed by the parliament (then still composed entirely of FRELIMO members) in 1992. Instead of receiving justice, victims were urged to forget.[45]

As part of the repressive measures following independence, FRELIMO introduced "reeducation centers" in which petty criminals, political opponents, and alleged anti-social elements such as prostitutes were imprisoned, often without trial. These were later described by foreign observers as "infamous centers of torture and death."[46] It is estimated that 30,000 inmates died in these camps.[47] The central government also executed tens of thousands of people while trying to extend its control throughout the country.[48][49][50]Rudolph Rummel estimated the democide of the FRELIMO government between 1975 and 1987 to lie between 83,000 and 250,000 dead, with a mid-level estimate of 118,000.[50][better source needed]

Aftermath[edit]

Transition to peace[edit]

In 1990, with the end of the Cold War, apartheid crumbling in South Africa, and support for RENAMO drying up in South Africa, the first direct talks between the FRELIMO government and RENAMO were held. FRELIMO's draft constitution in July 1989 paved the way for a multiparty system, and a new constitution was adopted in November 1990. Mozambique was now a multiparty state, with periodic elections, and guaranteed democratic rights.

On 4 October 1992, the Rome General Peace Accords, negotiated by the Community of Sant'Egidio with the support of the United Nations, were signed in Rome between President Chissano and RENAMO leader Afonso Dhlakama, which formally took effect on 15 October 1992. A UN peacekeeping force (UNOMOZ) of 7,500 arrived in Mozambique and oversaw a two-year transition to democracy. 2,400 international observers also entered the country to supervise the elections held on 27–28 October 1994. The last UNOMOZ contingents departed in early 1995. By then, the Mozambican civil war had caused about one million deaths and displaced over five million refugees out of a total population of ca. 13-15 million at the time.[12][13]

Landmines[edit]

HALO Trust, a de-mining group funded by the US and UK, began operating in Mozambique in 1993, recruiting local workers to remove land mines scattered throughout the country. Four HALO workers were killed in the subsequent effort to rid Mozambique of land mines, which continued to cause as many as several hundred civilian injuries and fatalities annually for years after the war. In September 2015, the country was finally declared to be free of land mines, with the last known device intentionally detonated as part of a ceremony.[51]

Resurgence of violence since 2013[edit]

In mid-2013, after more than twenty years of peace, RENAMO insurgency was renewed, mainly in the central and northern regions of the country. On September 5, 2014, former president Armando Guebuza and the leader of RENAMO Afonso Dhlakama signed the Accord on Cessation of Hostilities, which brought the military hostilities to a halt and allowed both parties to concentrate on the general elections to be held in October 2014. Yet, following the general elections, a new political crisis emerged and the country appears to be once again on the brink of violent conflict. RENAMO does not recognise the validity of the election results, and demands the control of six provinces – Nampula, Niassa, Tete, Zambezia, Sofala, and Manica – where they claim to have won a majority.[52]

On 20 January 2016, the Secretary General of RENAMO, Manuel Bissopo, was injured in a shootout, where his bodyguard died. However, a joint commission for the political dialogue between the President of the Republic, Filipe Nyusi, and RENAMO leader, Afonso Dhlakama, was eventually set up and a working meeting was held. It was a closed-door meeting that scheduled the beginning of the previous points that would precede the meeting between the to leaders.[53]

References[edit]

^ abcdefgh Arnold, Guy (2016). Wars in the Third World Since 1945. Oxford: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. pp. 211–213. ISBN 978-14742-9102-6.

^ Emerson (2014), pp. 90, 91.

^ abcde Bermudez, Joseph (1997). Terrorism, the North Korean connection. New York: Crane, Russak & Company. p. 124. ISBN 978-0844816104.

^ abcde Schwartz, Stephanie (2010). Youth and Post-conflict Reconstruction: Agents of Change. Washington, D.C: United States Institute of Peace Press. pp. 34–38. ISBN 978-1601270498.

^ War and Society: The Militarisation of South Africa, edited by Jacklyn Cock and Laurie Nathan, pp.104-115

^ ab "Afrikka" (PDF).

^ Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin. The Israeli connection: Whom Israel arms and why, pp. 65. IB Tauris, 1987.

^ abcde "Our work | Conciliation Resources". C-r.org. Archived from the original on 29 December 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

^ Bulletin of Tanzanian Affairs No 30, May 1988, pp 14

^ Mozambique to return bodies of Tanzanian soldiers, Panapress, 2004.

^ abcdef Vines, Alex (1997). Still Killing: Landmines in Southern Africa. New York: Human Rights Watch. pp. 66–71. ISBN 978-1564322067.

^ ab "Mozambique". State.gov. 4 November 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

^ ab "MOZAMBIQUE: population growth of the whole country". Populstat.info. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

^ Fauvet, Paul. "Mozambique's Renamo kills three on highway". iOl News. iOl News. iOl News. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

^ "36 Mozambique soldiers, police killed: Renamo". 13 August 2013. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

^ abcdefgh Derluguian, Georgi (1997). Morier-Genoud, Eric, ed. Sure Road? Nationalisms in Angola, Guinea-Bissau and Mozambique. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. pp. 81–95. ISBN 978-9004222618.

^ Sellström, Tor (2002). Sweden and National Liberation in Southern Africa: Solidarity and assistance, 1970–1994. Uppsala: Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-91-7106-448-6.

^ Walters, Barbara (1999). Snyder, Jack, ed. Civil Wars, Insecurity, and Intervention. Philadelphia: Columbia University Press. pp. 52–58. ISBN 978-0231116275.

^ abcde Sayaka, Funada-Classen (2013). The Origins of War in Mozambique: A History of Unity and Division. Somerset West: African Minds. pp. 263–267. ISBN 978-1920489977.

^ abc "MOZAMBIQUE: Dismantling the Portuguese Empire". jpires.org. Retrieved 4 March 2012. [permanent dead link]

^ Igreja 2007, p.128.

^ The cultural dimension of war traumas in central Mozambique: The case of Gorongosa. http://priory.com/psych/traumacult.htm

^ Lohman&MacPherson 1983, Chapter 4.

^ Igreja 2007 p.128f.

^ ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 30 December 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

^ Igreja 2007, p.153f.

^ ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 December 2011. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

^ ab "Defence Digest - Working Paper 3". Ccrweb.ccr.uct.ac.za. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

^ ab Zinsmeister, Karl. "All the Hungry People." REASON 20 (June, 1988): 22-30. p. 88, 28

^ ab Andersson, Hilary. MOZAMBIQUE: A WAR AGAINST THE PEOPLE. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1992. p. 64, 92

^ THE FACTS ON FILE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE 20TH CENTURY. New York: Facts on File, 1991. p. 91, 640

^ Gersony 1988, pp. 20-22

^ Gersony 1988, p.24-27

^ Gersony 1988, p. 32

^ "MHN: Homoine, 1987". Mozambiquehistory.net. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

^ "Jacob Alperin-Sheriff: McCain Urged Reagan Admin To Meet Terror Groups Without Pre-Conditions". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

^ Gersony 1988, p. 30f.

^ "Toll Over 380; Guerrillas Blamed : Massacre in Mozambique: Babies, Elderly Shot Down - Los Angeles Times". Articles.latimes.com. 16 August 1987. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

^ Gersony 1988, p.34-36.

^ Cahen 1998, p. 13.

^ http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.TAB14.1C.GIF Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder since 1900 by Rudolph Rummel, Lit Verlag, 1999

^ Mozambique HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPORT 1990

^ ab "War Traumas in Central Mozambique". Priory.com. 10 February 2007. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

^ Igreja 2007, p.150.

^ Igreja 1988, p.20-22.

^ Peter Worthington, "Machel Through Rose-Tinted Specs," Financial Post (Canada), November 1, 1986

^ Geoff Hill, "A Crying Field to Remember," The Star (South Africa), November 13, 2007

^ Hoile, David. MOZAMBIQUE: A NATION IN CRISIS. Lexington, Georgia: The Claridge Press, 1989. p 89, 27-29

^ Katz, Susan. "Mozambique: a leader's legacy: economic failure, growing rebellion." INSIGHT (November 10, 1986): 28-30. p 86, 29

^ ab http://www.hawaii.edu/powerkills/SOD.TAB14.1C.GIF

^ Smith, David (17 September 2015). "Flash and a bang as Mozambique is declared free of landmines". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 September 2015.

^ https://www.academia.edu/19787524/Provincial_Autonomy_The_Territorial_Dimension_of_Peace_in_Mozambique

^ https://www.academia.edu/28536746/PORQU%C3%8A_O_CONFLITO_ARMADO_EM_MO%C3%87AMBIQUE_ENQUADRAMENTO_TE%C3%93RICO_DOMIN%C3%82NCIA_E_DIN%C3%82MICA_DE_RECRUTAMENTO_NOS_PARTIDOS_DA_OPOSI%C3%87%C3%83O

Bibliography[edit]

This article includes a list of references, but its sources remain unclear because it has insufficient inline citations. (August 2009) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

- Cabrita, João M., Mozambique: The Tortuous Road to Democracy (London: Palgrave, 2000).

- Cahen, Michel, "Dhlakama E Maningue Nice!": An Atypical Former Guerrilla in the Mozambican Electoral Campaign, Transformation, No. 35, 1998, p.1-48.

Emerson, Stephen A. (2014). The Battle for Mozambique: The Frelimo–Renamo Struggle, 1977–1992. Solihull, Pinetown: Helion & Company, 30° South Publishers. ISBN 978-1-909384-92-7.- Gersony, Robert, Report of Mozambican Refugee Accounts of Principally Conflict-Related Experience in Mozambique, U.S. Department of State, 1988.

- Igreja, Victor, The Monkey's Sworn Oath. Cultures of Engagement for Reconciliation and Healing in the Aftermath of the Civil War in Mozambique, Leiden: PhD Thesis, 2007 (online at: https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/12089)

- Juergensen, Olaf Tataryn. 1994. Angonia: Why RENAMO?. Southern Africa Report Archive

- Lohman, Major Charles M.; MacPherson, Major Robert I. (7 June 1983). "Rhodesia: Tactical Victory, Strategic Defeat" (pdf). War since 1945 Seminar and Symposium (Quantico, Virginia: Marine Corps Command and Staff College). Retrieved 19 October 2011.

- Morier-Genoud, Eric, Cahen, Michel and do Rosário, Domingos M. (eds), The War Within New Perspectives on the Civil War in Mozambique, 1976-1992 (Oxford: James Currey, 2018)

- Young, Lance S., Mozambique's Sixteen-Year Bloody Civil War. United States Air Force, 1991

External links[edit]

- Text of all peace accords for Mozambique

Mozambique-US Relations during Cold War from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

Categories:

- Wars involving the states and peoples of Africa

- 20th-century conflicts

- History of Mozambique

- Guerrilla wars

- Wars involving South Africa

- Civil wars involving the states and peoples of Africa

- Civil wars post-1945

- Revolution-based civil wars

- Mozambican Civil War

- Wars involving Mozambique

- Wars involving Zimbabwe

- Wars involving Tanzania

- Wars involving Rhodesia

- Wars involving Malawi

- Wars involving communist states

- Communism-based civil wars

- Proxy wars

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function()mw.config.set("wgPageParseReport":"limitreport":"cputime":"0.712","walltime":"0.913","ppvisitednodes":"value":4666,"limit":1000000,"ppgeneratednodes":"value":0,"limit":1500000,"postexpandincludesize":"value":195862,"limit":2097152,"templateargumentsize":"value":10828,"limit":2097152,"expansiondepth":"value":12,"limit":40,"expensivefunctioncount":"value":26,"limit":500,"unstrip-depth":"value":0,"limit":20,"unstrip-size":"value":42859,"limit":5000000,"entityaccesscount":"value":0,"limit":400,"timingprofile":["100.00% 586.284 1 -total"," 29.57% 173.355 1 Template:Reflist"," 18.42% 107.970 1 Template:Infobox_military_conflict"," 18.30% 107.262 7 Template:Navbox"," 13.49% 79.070 1 Template:Mozambique_topics"," 12.97% 76.035 1 Template:Country_topics"," 11.52% 67.516 9 Template:Cite_book"," 7.86% 46.063 12 Template:Cite_web"," 7.67% 44.972 3 Template:Fix"," 7.47% 43.824 2 Template:Better_source"],"scribunto":"limitreport-timeusage":"value":"0.203","limit":"10.000","limitreport-memusage":"value":6209195,"limit":52428800,"cachereport":"origin":"mw2241","timestamp":"20180916132828","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false);mw.config.set("wgBackendResponseTime":94,"wgHostname":"mw2256"););

Clash Royale CLAN TAG

Clash Royale CLAN TAG