Ludwigsburg Palace

Ludwigsburg Palace

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

- This article is about the residential palace. For the other palace on the same grounds, see Schloss Favorite, Ludwigsburg. For the city, see Ludwigsburg. For the porcelain manufactory, see Ludwigsburg Porcelain Manufactory.

| Ludwigsburg Palace | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

German: Residenzschloss Ludwigsburg | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ludwigsburg Palace and the Blooming Baroque gardens seen from the south | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Ludwigsburg Palace (German: Residenzschloss Ludwigsburg), also known as the "Versailles of Swabia", is a 452-room palace complex of 18 buildings located in Ludwigsburg, Germany, built for the dukes of Württemberg. With the added gardens around the palace, Ludwigsburg Palace's total area amounts to 32 ha (3,400,000 sq ft), making it the largest palatial estate in Germany.[1][2] In 2016, the Ludwigsburg Palace attracted some 330,000 visitors.

The first phase of construction lasted from 1704 to 1733 under Philipp Jenisch, Johann Nette, and Donato Frisoni and cost 3,000,000 florins. Modifications by Philippe de La Guêpière and Friedrich von Thouret then followed from 1750 to 1824. As a result, Ludwigsburg Palace is a combination of the Baroque, Rococo, Neoclassical, and French Empire styles. The palatial architecture, especially the Baroque elements present, exhibit strong influence from Austria, Bohemia, and France, as Ludwigsburg was inspired by the Palace of Versailles but was built by students of the Bohemian Baroque school. In 1918, the palace was opened to the public and was used as a venue during the ratification of the constitution of the Free People's State of Württemberg the next year. It then survived the Second World War intact, the only palace of its kind to do so, and underwent periods of restoration in the 1950s, 1960s, and 1990s and again for the palace's 300th anniversary in 2004. Every year since 1947 the palace has hosted the Ludwigsburg Festival.

Surrounding the palace on three sides are the Blooming Baroque (German: Blühendes Barock) gardens, opened in 1954 for the palace's 250th anniversary, arranged as it might have appeared in 1800. Nearby is Schloss Favorite, a hunting lodge built in 1717 by Donato Frisoni. Within the palace itself are two museums operated by the Landesmuseum Württemberg. A porcelain manufactory, producing the Ludwigsburg porcelain, operated in the palace from 1758 to 1824.

Contents

1 History

1.1 Construction

1.2 Use as a residence

1.3 Later history

2 Porcelain manufactory

3 Architecture

3.1 Old Hauptbau

3.2 East wing

3.3 West wing

3.4 New Hauptbau

4 Grounds and gardens

4.1 Schloss Favorite

4.2 Museums

5 See also

6 Notes

6.1 Footnotes

6.2 Citations

7 References

7.1 Online references

8 External links

History[edit]

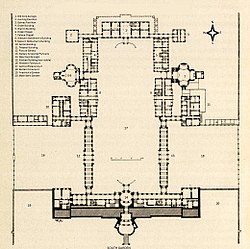

1889 plan of Ludwigsburg Palace, as completed. 1: Old Hauptbau. 2 & 3: Hunting and Pleasure Pavilions. 4: Ordensbau. 5: Riesenbau. 6: Ordenskapelle. 7: Schlosskapelle. 8 & 9: West and East Kavaliersbauten. 10: Festinbau. 11: Schlosstheater. 12: Bildergalerie. 13: Ahnengalerie. 14: New Hauptbau. 15: Kitchens (not visible). 16: West Forecourt. 17: Central Courtyard. 18: East Forecourt. 19: Friedrich Garden. 20: Mathilde Garden.

In the 17th century, the land that Ludwigsburg Palace was to occupy was a hunting property with a lustschloss called the Erlachhof, which was destroyed by French troops in 1692 during the Nine Years' War. In the spring of 1700, Duke Eberhard Louis tasked his then court architect Matthias Weiss, a military architect, with the Erlachhof's replacement with a new lustschloss. The duke then went on a tour of England and Holland for inspiration. Weiss planned and began construction of a three-story manor but was interrupted by the outbreak of the War of the Spanish Succession. The war culminated in the decisive Battle of Blenheim, where Eberhard Louis commanded a cavalry regiment.[3][4] Dreaming of his own absolutist state, he felt inspired by the palaces of Munich, where he spent the remainder of 1705 into early 1706.[5][4] Eberhard Louis decided to build one of his own, and a new township to match, that would capture his prestige and hopefully win him the coveted title of Elector.[3][6]

The Old Hauptbau in 1705

The Erlachhof's reconstruction gave Eberhard Louis a pretext for this new palace,[7] so he renamed the estate after himself (German: Ludwigsburg, lit. 'Louis's Castle'), and the duke began educating himself on the architectural trends of his day.[8] The massive undertaking of the palace's construction eventually necessitated the building of a city, which would also be known as Ludwigsburg.[9][6] Eberhard Louis decided to cut construction costs, for example allowing construction workers to settle in the city from 1709 on,[10] then made overtures to potential settlers such as financing for construction material, property, and 15 years without taxation for the residents of Ludwigsburg.[6][a] To recoup some of the cost of that financing, Duke Eberhard Louis commanded the city's residents to either kill several dozen of the sparrows that plagued the city or pay at least six Kreuzer to the duke's construction treasury (German: Baukasse).[6] Today, the Schlosstheater is itself a museum containing restored Baroque theater props and backgrounds.[11] Construction and growth of the town stalled from its opening in 1709 until Eberhard Louis granted Ludwigsburg city status in 1718 and established it as the capital of the Duchy of Württemberg.[6]

Construction[edit]

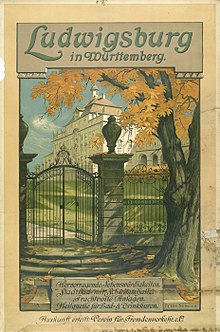

An 1896 German lithograph depicting the palace

Duke Eberhard Louis sent theologian and mathematician Philipp Joseph Jenisch to study architecture abroad in 1703, then made Jenisch director of the palace's construction on his return.[12][13] Jenisch worked from Weiss's plans and work, but construction was throttled by Württemberg's entry into the War of the Spanish Succession. Jenisch only finished the floor and walls of Weiss's lustschloss and some of the southern garden.[14][4] Eberhard Louis's stay at the palaces of the Bavarian Electors at Munich in 1705 following the Battle of Blenheim heralded the end of Jenisch's tenure at Ludwigsburg, as the duke came to the conclusion that Jenisch could not match the splendor of Nymphenburg Palace. In early 1707, Eberhard Louis replaced him with 23 year-old Johann Friedrich Nette of Brandenburg,[13] whose task it was to build a complete Baroque palace from Jenisch's corps de logis, to which the wings were aligned at 11°. His work would be further complicated by the palace's foreman,[4] Johann Ulrich Heim, an ally of Jenisch who would oppose Nette and the growing number of Italian artists at the palace until 1714.[12] Opposition to the palace itself was found at the duchy's court because of its exorbitant cost.[15] The populace also chafed at the palace's cost, one pastor in nearby Oßweil saying of the palace at his pulpit, "May God spare our land the chastising that the Ludwigsburg brood of sinners conjure."[4]

Courtyard, looking north at the corps de logis of the Old Hauptbau. Nette began and finished most of the structures depicted.

Nette based his plans on those of Jenisch, enabling him to complete his design for a three-wing palace in the same year as his appointment. The galleries of the Old Hauptbau were completed in 1707, then its corps de logis the next year. Absorbing Weiss and Jenisch's lustschloss, the Ordensbau was constructed from 1709 to 1713 and the Riesenbau from 1712 into the next year. The interiors of these structures, which included dining halls in each beletage, were completed in 1714 while Nette began the interior of the Old Hauptbau (which he would never finish). Construction of the Old Hauptbau's pavilions would drag on into 1722.[16][4] Nette made two trips to Prague and his native Brandenburg to expand his pool of talent, in 1708 hiring fresco painter Johann Jakob Stevens von Steinfels, stucco workers Tomasso Soldati and Donato Giuseppe Frisoni, then in 1709 Andreas Quitainner and later Luca Antonio Colomba, Riccardo Retti and Diego Carlone. Nette fled due to an accusation of embezzlement from Jenisch's allies to Paris, but was ordered back to Ludwigsburg by Eberhard Louis. On his return trip, he died suddenly of a stroke on 9 December 1714 in Nancy, aged 41. At the time of his death, most of the northern section of the modern palace and its northern garden had been completed.[4][17]

The New Hauptbau's corps de logis seen from the courtyard

Jenisch sought to reprise his position as building director following Nette's death, and the building authority was aligned with him.[18] However, Eberhard Louis overruled them in 1715 and appointed Donato Frisoni,[19] a plasterer from Laino who had no formal architectural training. An earlier application Frisoni had made for the directorship had been ignored by the building authority, but he enjoyed the support of the Court Chamberlain and had impressed the Duke with the delicate Bandlwerkstil stucco that Frisoni and Soldati had decorated the Old Hauptbau's interiors with.[4][20] Frisoni, too, finished his plans in the year of his appointment by working from Nette's and began his work with the palace's churches, the Catholic Schlosskapelle in 1716 and the Lutheran Ordenskapelle in 1720.[b] Next, Frisoni finished the East and West Kavaliersbauten (Cavaliers' Buildings) in 1722 to house the courtiers of Eberhard Louis's court.[14][23] Frisoni also added the mansard roof to the top of the Old Hauptbau because the original flat roof was prone to water damage. This had become a common issue with Nette's work because of the pressure the duke placed on him to finish the palace as soon as possible.[24][25] Frisoni's work thus far led him to the same conclusion as Nette: that he did not have a suitable talent pool to accommodate the duke's desires for the palace and city, so Frisoni brought on Giacomo Antonio Corbellini and Paolo Retti, his brother and son-in-law respectively, who were followed by Diego Francesco Carlone in 1718.[4]

Beginning in 1721, the duke began to run out of room for the functions of his court in the Old Hauptbau and Frisoni began planning to enlarge it.[4] Three years later, the duke dismissed the idea and ordered Frisoni to construct what would become the New Hauptbau. Frisoni originally designed a four story structure, double the height of the existing palace, but plans would change several times after construction began in 1725 atop the first terrace of the south garden. Frisoni settled on a three-story building that still afforded the duke six rooms for his suite to the Old Hauptbau's three. To connect the New Hauptbau to the existing palace, Frisoni built the Bildergalerie and Festinbau on the west side, and the Ahnengalerie and Schlosstheater on the east. The Bildergalerie was decorated in 1731 and 1732 with stucco and fresco by Pietro Scotti and Giuseppe Baroffio (also at work remodeling the Ordensbau at this time), while the Ahnengalerie was likewise decorated by the Carlone brothers from 1731 to 1733. With the exception of the interiors of the New Hauptbau and Schlosstheater, all work was finished in 1733,[26], but Eberhard Louis died that same year[27] with only a few rooms in the west end of the New Hauptbau completed.[22] Construction of the New Hauptbau and its connecting galleries cost 465,000 guilders and was managed by Paolo Retti, who at times had more than 650 stone masons, cutters, and basic laborers working on the facades between 1726 and 1728.[4] In totality, the construction of Ludwigsburg Palace cost the Duchy of Württemberg 3,000,000 florins.[28]

Use as a residence[edit]

View of the main palace from Schloss Favorite

As Duke Eberhard Louis left no heirs, he was succeeded by the Catholic Karl Alexander, also a military leader.[4] While he did lay out a new garden at Ludwigsburg,[29] Karl Alexander ended funding for the palace, dismissed its staff, and moved the capital back to Stuttgart in 1733 to modernize Württemberg's army and fortifications.[4][22] Foreign workers at the palace, called Welschen, had been disliked and envied by native German courtiers. As the master builder of what was now decried as the "sin palace", Donato Frisoni was arrested in 1733 with Paolo Retti on fraudulent charges of embezzlement. The two men were acquitted in 1735 after they paid a hefty fine to the ducal treasury, despite attempted intervention by the Margrave of Ansbach to free them earlier, but Frisoni died in the city on 29 November 1735.[19][18] Karl Alexander himself died suddenly two years later on 12 March 1737, as he prepared to leave Ludwigsburg Palace to inspect the duchy's fortresses. Unlike Eberhard Louis, Karl Alexander did have an heir in Charles Eugene, but he was only nine when Karl Alexander died, beginning a regency that would last until 1744.[30]

In 1760, Casanova was a guest at Charles Eugene's court. During his stay, he praised the performances of the duke's orchestra.[31]

In 1746, Charles Eugene began the construction of a new ducal residence in Stuttgart, but he continued to use Ludwigsburg as a secret residence from 1746 to 1775 and brought the Rococo style to Ludwigsburg the next year. The use of certain rooms at Ludwigsburg could change frequently, such as when the duke tasked Johann Christian David Leger with the permanent conversion of the Ordenskapelle to a Lutheran church for Elisabeth Fredericka Sophie of Prussia from 1746 to 1748. Beginning in 1757 and lasting into the next year, the suites of the beletage were extensively modified under Philippe de La Guêpière, the duke's new court architect.[32][4][33] Charles Eugene finished the Schlosstheater from 1758 to 1759 through La Guêpière,[34], who erected a stage and auditorium as well as stage machinery.[11] An avid fan of opera like his father,[29] from 1764 to 1765 Charles Eugene also constructed a wooden opera hall richly adorned with mirrors, which was located east of the Old Hauptbau.[4] In 1764, Charles Eugene moved the ducal residence back to Stuttgart and made no more modifications to Ludwigsburg from 1770 onward. The palace, which hosted a court that Giacomo Casanova called "the most magnificent in Europe", began a steady decline.[34][31]

Frederick I's throne in the Ordensbau

In 1793, Charles Eugene died without a legitimate heir and was succeeded by his brother, Frederick II Eugene, who was himself succeeded by his son Friedrich II in 1797. Ludwigsburg Palace had already been the residence of Friedrich II since 1795,[4] and Friedrich II declared it his summer residence.[34] On 18 May 1797, Friedrich II married Charlotte of Great Britain, daughter of King George III, at St James's Palace in Westminster.[35] They used Ludwigsburg as their summer residence, Frederick taking a suite of 12 rooms west of the Marble Hall and Charlotte a dozen to its east,[27], but the duke did not have time to remodel the suites, which were by that time out of style.[4]

Napoleon Bonaparte's armies occupied Württemberg from 1800 to 1801, forcing the duke and duchess to flee to Vienna. The royals returned when Friedrich II agreed to pledge allegiance to Napoleon and part with some territory in exchange for the title of Elector in 1803.[35] Friedrich II, now Frederick I, felt that he had to express this accomplishment in architecture, as Eberhard Louis had attempted, and gave his court architect Nikolaus Friedrich von Thouret the task of updating the palace in the Neoclassical style, beginning with the Ahengalerie from 1803 to 1806 and the Ordensbau from 1804 to 1806.[36] For two days in October 1805,[37] Napoleon visited Ludwigsburg to coerce Frederick I into joining the Confederation of the Rhine and thus becoming his ally,[38]compensating Württemberg with neighboring territories in the Holy Roman Empire and Frederick I with the title of King.[36] Frederick I again tasked von Thouret with a remodeling, this time the Ordenskapelle and the king's apartment, which lasted from 1808 to 1811. The final modernizations ordered by the king took place from 1812 to 1816, and were the remodeling of the Schlosstheater and Marble Hall and the repainting of the ceilings of the New Hauptbau's main staircases and the Guard Room. When Frederick I died in 1816, the majority of the palace had been converted to reflect then-modern tastes.[39]

Following her husband's death, Charlotte continued to reside at Ludwigsburg and received many notable visitors from across Europe, among them some of her siblings.[40] She tasked von Thouret with the renovation of her own apartment, which took place from 1816 to 1824.[41] The dowager queen died on 5 October 1828 following a bout of apoplexy and was interred in the Württemberg family vault.[42] The queen was the last ruler of Württemberg to reside at Ludwigsburg, as Frederick's son and successor, William I, and future kings did not show any interest in the palace.[41]

Later history[edit]

Borkum Island Massacre trial, 1946. Pictured is the defense attorney addressing the court, set up in the Ordensbau's Order Hall.

In 1817, ownership of Ludwigsburg Palace passed from the House of Württemberg to the state government, which established offices there the next year.[43] King William I chose the Order Hall, the throne room of his father, for the ratification of the Kingdom of Württemberg's constitution in 1819.[44] In the same time period that the first restoration at the palace took place, 1865 in the Old Hauptbau, the Order Hall was being used as a courtroom, and members of the royal family continued residing at the palace into the early 20th century.[43] In 1918, the palace was opened to the public and the following year saw the ratification of the constitution of the Free People's State of Württemberg.[45][44] Four years later, the Schlosstheater hosted a production of Händel's Rodelinda by the Württemberg State Theatre, its first musical performance since 1853. In the early 1930s, Wilhelm Krämer began holding the Ludwigsburg Palace Concerts (Ludwigsburger Schlosskonzerte) that, from 1933 to 23 July 1939, annually comprised six to ten concerts held in the Order Hall, the Ordenskapelle, or the courtyard.[45] The palace survived the Second World War unscathed and was chosen as the site of the Borkum Island war crimes trial.[43][46] The concerts resumed in 1947 with 34 performances, a record that would not be broken until 1979. In 1952, the concerts were packed into a single week as the "Palace Days" (Ludwigsburger Schlosstage) and gained national significance when Theodor Heuss attended a production of Mozart's Titus two years later. The Palace Days became the Ludwigsburg Festival in 1966, which was attended by 12,000 visitors. Finally, in 1980, the state of Baden-Württemberg made the festival an official state event.[45]

Revolverheld performing in the courtyard.[47]

Restorations were undertaken in the 1950s and 60s and again in the 1990s,[43] in time for the palace's 300th anniversary in 2004. The anniversary was commemorated by the state government with three new museums and by the Federal government with a postage stamp depicting the palace in the same year.[43][48][49] On 19 October 2011, Minister-President Winfried Kretschmann hosted a reception for the US 21st Theater Sustainment Command at the palace that was attended by John D. Gardner, former deputy commander of EUCOM, and Gert Wessels, commander of all Federal troops in Baden-Württemberg.[50] Almost five years later on 16 August 2016, Baden-Württemberg's Minister of Finance, Edith Sitzmann, visited Ludwigsburg Palace and Schloss Favorite as part of a castle tour.[51]Ulm-based group Klötzlebauer exhibited a number of their Lego creations, attracting 18,000 visitors and prompting them to exhibit at the palace again that winter.[52][53] In that time, Ludwigsburg appeared again in Federal postage stamps in the "Burgen und Schlösser" stamp series.[54] In November 2017, a painting of Frederick the Great on display in Duke Charles Eugene's apartment and attributed to Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff was found to have actually been painted by his teacher, Antoine Pesne. Michael Hörrmann, the director of the State Agency for Palaces and Gardens, valued the portrait at a minimum of €1 million, as one officially done by Pesne.[55] Sitzmann returned to the palace to see the painting and to attend a press conference, where she spoke about the cultural importance of Ludwigsburg Palace.[56]

By October 2017, 311,000 people visited Ludwigsburg Palace. It was projected that 350,000 people would visit by the end of that year, as 330,000 had done so in 2016. By March 2020,[57] the Baden-Württemberg State Agency for Palaces and Gardens plans to have spent €4 million to sort out and restore some 500 paintings, 400 pieces of furniture, and 500 lamps, clocks, and sculptures and arrange them to make the entire New Hauptbau appear as it would have looked in the reign of King Frederick I.[55][56] Using inventory lists from the 19th century, palace staff are arranging the New Hauptbau to its Classical-era appearance and acquiring items from the palace that were present on location in the mid-19th century.[58]

Porcelain manufactory[edit]

Cello-player, modelled by Johann Wilhelm Beyer, 1760s

In 1729, Duke Eberhard Louis received an offer from a mirror-maker named Elias Vater to found a porcelain manufactory, but the Duke turned down his offer, thinking it ridiculous. Eberhard Louis's successor, Charles Alexander, heard of the proposal and in 1736 set aside 2000 gulden for experimenting with the production of porcelain under one Johann Philipp Weißbrodt, which were failures and ceased entirely when Charles Alexander died. Charles Eugene succeeded the throne following a regency and in 1751 passed a decree allowing the Calwer Handelscompagnie von Zahn und Dörtenbach to utilize all the duchy's previous research to again attempt to manufacture porcelain, a right they possessed until its transferral in 1857. Charles Eugene officially founded the Ludwigsburg Porcelain Manufactory on 5 April 1758 to pressure his Handelscompagnie into delivering, but both parties would fail because of setbacks and insufficient funding. Early progress was hindered by poor handling of raw material and debate over production. Charles Eugene hired Joseph Jakob Ringler, who had worked previously in Vienna, Nymphenburg, and Höchst, on 16 February 1759 as head of the Ludwigsburg Porcelain Manufactory. Ringler held this position for 40 years.[59][60]

Ludwigsburg porcelain, 1770s, Hallwyl Museum, Stockholm

Ringler almost immediately began production of Ludwigsburg's signature grey-brown porcelain, and by March 1758 had 21 employees under him. Over his long career in porcelain, Ringler had learned the proper mixture and technique for making porcelain, but had also made connections to artisans in the business, which allowed him to convince Duke Charles Eugene to hire master painter Gottlieb Friedrich Riedel, from the Meissen manufactory, and the sculptor Johann Wilhelm Beyer. The manufactory's first years were very successful, making it one of the biggest producers of porcelain wares in Europe from 1760 to 1775. Despite this success, the company regularly spent more than its income, forcing Charles Eugene to support it himself even after he moved the Ducal residence back to Stuttgart from the palace complex in 1775, though he curtailed his support of the company in 1771. Charles Eugene was succeeded in 1793 by Louis Eugene, and he put the manufactory's affairs in order. However, the repaying of its debts and further support of the company by Frederick II Eugene from 1797 could not stall the manufactory's decline. Since 1780, tastes in porcelain artisanry, and by extension the industry, moved from Rococo to the Louis XVI style, but Riedel and thus his department of painters would not adjust to the demand. The company enjoyed a brief renaissance in the reign of King Frederick I, but it went into rapid decline on the King's death in 1816. King William I was not interested in propping up the failing company, and it finally closed in 1824 when no buyer or leaseholder was found.[59][60]

Architecture[edit]

Ludwigsburg Palace exhibits a great deal of Austro-Czech influence,[61] attributable to Johann Friedrich Nette and Donato Frisoni, who were educated in and experienced with Bohemian Baroque architecture and hired staff also experienced in the Bohemiam Baroque style.[19] Some French influence is also present, visible in the mirror halls in both corps de logis and the mansard roofs, but the combination of work by Germans Philipp Jenisch and Nette and Italians Donato Frisoni, Diego and Carlo Carlone, Giuseppe Baroffio, Pietro Scotti and Luca Antonio Columba produced a strong resemblance to late 17th century works in Prague and Vienna.[24][62] The interiors are also a mix of Baroque influences from Paul Decker the Elder, Nicodemus Tessin the Elder, and Daniel Marot, whose work Duke Eberhard Louis was familiar with and bears some resemblance to Ludwigsburg's ribbonwork (Bandlwerkstil) stucco.[23] Ludwigsburg's Neoclassical architecture, inspired by the Renaissance, the work of Charles Percier and Pierre François Léonard Fontaine, and Egyptian motifs that became popular in Europe with Napoleon's three-year campaign in Egypt, does not reflect a single style or designer. King Frederick I, at the time Duke Friedrich II, gave Nikolaus Friedrich von Thouret the task of remodeling Ludwigsburg's interiors in the Neoclassical style. Thouret was inspired by the French Imperial style, but his friend and partner Antonio Isopi simplified Thouret's plans into a more grounded Classical form that would then be carried out by Johannes Klinckerfuß and court painter Jean Pernaux.[39]

Old Hauptbau[edit]

A mirror in the Spiegelkabinett, Duke Eberhard Louis's apartment

The Old Hauptbau, forming the corps de logis of the north wing, is the oldest portion of the palace, originally built just to house the apartments of Duke Eberhard Louis and his daughter-in-law, Princess Henrietta Maria of Brandenburg-Schwedt.[63] Its facade was built in a three year period from 1705 to 1708, and the work on its interiors was mostly completed by 1715 under Donato Giuseppe Frisoni, while work inside its pavilions lasted into 1722. In 1809 and 1826–28, the rooms facing the courtyard in the beletage were remodeled in Neoclassical, but their Baroque frescoes were revealed in 1865. The corps de logis has a wide vestibule and stairs that terminate in a guard room in the beletage. It houses four suites, which follow the French Baroque model of a living room, audience chamber, and bedroom. Eberhard Louis's apartment is made unique by the addition of a hall of mirrors decorated with stucco by Donato Frisoni and a hidden staircase (since removed) into the room of Eberhard Louis's mistress Wilhelmine von Grävenitz.[64][63] The third floor was finished in 1708 and houses the two picture galleries. The first takes up most of the south wall and served as an ahnentafel and portrait gallery before the construction of the southern portion of the complex by Frisoni. Most of the stucco and fresco work, depicting biblical and mythological motifs alongside an image of Eberhard Louis and his monogram, were lost when the gallery was subdivided into offices and until its restoration from 2000 to 2004.[65] Above the third floor is a mansard roof that now houses a preserved piece of clockwork taken from Zwiefalten Abbey by King Frederick I in 1809.[24]

The Spielpavillon, looking down the Eastern Gallery. Visible are some of the Delftware Callot dwarves.

The two pavilions to the west and east of the Old Hauptbau are joined to the corps de logis by arcaded galleries that close off the northern edge of the cour d'honneur.[14] Completed in 1713 and 1715 respectively, they begin with pilastered doorways on either side of the Old Hauptbau's second floor. The Western Gallery celebrates peacetime with plaster statuary and medallions displaying certain virtues, and reliefs of the Judgement of Paris, Aeneas fleeing Troy, Hercules and Omphale, and Apollo and Daphne. Its terminus is the Jagdpavillon (Hunting pavilion), containing the Marmorsaletta (German; lit. 'Little marble hall'), decorated with scagliola by Riccardo Retti and frescoes by Luca Antonio Colomba. Adjoined to the hall are the Boiserie, Marble, and Lacquer Cabinets. The first and third rooms are examples of Baroque exoticism, as the Boiserie Cabinet is decorated in Turkish motifs and the Lacquer Cabinet in imitation Chinese imagery against black backgrounds.[66][67] The Eastern Gallery celebrates warfare with pairs of trophy captives and weapons, Eberhard Louis's monogram, and stucco reliefs depicting the virtues of Strength, Justice, Moderation, and Wisdom and the classical elements. Above the entire gallery is Colomba's Gigantomachy, the war between the Twelve Olympians and the Giants. The Spielpavillon, at the end of the Eastern Gallery, was completed in 1716 by Frisoni according to designs by himself and Nette (whose plans were used for the exterior). In its center is a rounded, cruciform hall with four corner-rooms that contain imitation-Delftware images of Jacques Callot's Grotesque Dwarves. Hemmed in with stucco ribbonwork and reliefs of cherubs, the dome fresco by Colomba and Emanuel Wohlhaupter depict the four seasons and their corresponding zodiac signs.[68][69]

East wing[edit]

The Riesenbau's eponymous giants in its vestibule

The Riesenbau (Giants' Building), built by Johann Friedrich Nette from 1712 to 1713, begins the east wing of Ludwigsburg Palace. The vestibule was decorated by Andreas Quittainer and Luca Antonio Colomba. It prominently features two sphinxes and four giants as the atlases under the staircase to the beletage, originally intended to lead up into a room for the Hunting Order that was segregated into residences from 1720 to 1723. Ahead of the giants is a statue of Minerva, and the frescoes on the ceiling above the staircase show Justitia and Fortitudo, the four seasons, and the four classical elements. In 1810, the rooms on the beletage were remodeled in Neoclassical, but they were restored to the Baroque style and opened as a museum in the 1950s. The apartments of Frederick Louis and Carl Alexander were decorated by Frisoni and Colomba, but Carl Alexander's apartment also features a landscape painting by Adolf Friedrich Harper.[70]

View of the Schlosskapelle's altar from the Duke's box

Joined to the Riesenbau and East Kavaliersbau (Cavaliers' Building) by a connecting room on its southern end is the Schlosskapelle (Palace chapel), built from 1716 to 1724 and consecrated in 1723. The chapel is made up of a rotunda with three semi-domes and a private box for the Duke and his family, accessed from the second floor. The box was painted around 1731 with the story of King David and given its red velvet wallpaper and a ceiling fresco by Livio Retti. The chapel itself was painted by Frisoni, Colomba, and Carlo Carlone, who were restricted by Protestant doctrine to illustrations of the Apostles and scenes from the Old Testament. Beneath the chapel is a crypt that contains all rulers of Württemberg from Eberhard Louis to Frederick I. The Schlosskapelle avoided major remodeling in the 19th century, and is today the most original structure of any area of the residential palace.[71][21] The original organ, built in 1724 by organ builder Joseph Friedrich Baumeister and installed in 1747 by Georg Friedrich Schmahl, was moved to the Ordenskapelle in 1798 by Johann Jakob Pfeiffer. A new organ was built in 1916 by the Walcker Orgelbau company, and today the original one is still extant at Schöntal Abbey.[72]

The Ahnengalerie, in the New Hauptbau

Directly south of the Riesenbau is the East Kavaliersbau, built from 1715 to 1719 to house members of the Ducal court. It contains four apartments on both floors, like the West Kavaliersbau, and is decorated with stucco ornament by Riccardo Retti and a fresco on the ceiling of the beletage by Leopoldo Retti, preserved from the 1720s. The southwestern apartment on the second floor contains a museum dedicated to the Schlosstheater, attached by gallery to the East Kavaliersbau and the Schlosskapelle. It was constructed by Frisoni from 1729 to 1733, making it Europe's oldest preserved theater, but it was not furnished until 1758–59 by Philippe de La Guêpière, who added the stage, auditorium, and machinery. Friedrich von Thouret remodeled the Schlosstheater in Neoclassical in 1811–12.[73][11]Casanova is known to have visited the Schlosstheater,[74] making notes on the performances held there.[75]

The final and southernmost part of the east wing is the Ahnengalerie, built in 1729. It spans the 490 feet (150 m) gallery bridging the work of Nette and Frisoni to the New Hauptbau. The ceiling frescoes by Carlo Carlone were to depict the story of Achilles, but Eberhard Louis decided to move that fresco to the Bildergalerie after the completion of the first and last frescoes in the series in 1732. In the place of this and Frisoni's original plan for a modest and plain white hall, Carlone painted an homage to Eberhard Louis in 1731–33 to glorify and depict his reign with depictions of Alexander the Great and Apelles, Venus, Mars, Apollo, Phobos, and the Muses, among others. Frederick I had von Thouret remodel the Ahnengalerie in 1805–06, retaining Carlone's frescoes and adding additional stucco to the two antechambers. The portraits in the Ahnengalerie trace the lineage of the rulers of Württemberg from Eberhard I the Bearded, first Duke of Württemberg, to Wilhelm II, the last King of Württemberg, as well as some wives of the Dukes and Kings of Württemberg.[76][77]

West wing[edit]

The Order Hall, on the second floor of the Ordensbau

Beginning the west wing is the Ordensbau (Order building), containing three apartments on the ground floor and the banquet hall of the Duke's hunting order, later called the Order of the Golden Eagle. The vestibule is decorated with a ceiling fresco of Pheme with a genius, while pictures of Hercules adorn the wall and continue into the stairwell. The antechamber to the Order Hall is populated with stucco reliefs of cherubs, masks, birds, and weapons by Tomasso Soldati and Donato Frisoni. The Order Hall's stucco was also by Tomasso and Frisoni, but the ceiling fresco is a later repainting by Pietro Scotti and Giuseppe Baroffio in 1731 as Colomba's was damaged by water and removed. King Frederick I had the Hall renovated into a throne room in 1805–06, moving the function and imagery of the Order of the Golden Eagle to the Ordenskapelle. Friedrich von Thouret designed Frederick I's throne and baldachin, opposite Johann Baptist Seele's 1808 portrait of the King. It was in the Order Hall that the constitutions of the Kingdom (1819) and then Free People's State of Württemberg (1919) were ratified.[78][44][79]

King Frederick I's throne in the Ordenskapelle

Immediately southwest of the Ordensbau is the oval Ordenskapelle (Order chapel). It was begun in 1720 as a companion to the Schlosskapelle, but was converted to its current functionary purpose from 1746 to 1748 by Duke Charles Eugene, who tasked Johann Christoph David Leger with remodeling it for Duchess Elisabeth Fredericka. Leger removed the floor between the chapel and a second-floor Order hall and reused the existing pilasters for new Rococo decor crafted by Pietro Brilli. Livio Retti painted frescoes of the life and times of Jesus Christ on the ceilings of the chapel. Above, on the second floor, is the Duchess' box, opulently decorated in 1747–48 with stucco and frescoes of the birth of Christ and allegories of faith, hope and love. In 1798, Frederick I moved the Ordenskapelle's church functions to the Schlosskapelle. Nine years later as king, he designated it for use by the Order of the Golden Eagle and tasked Friedrich von Thouret with remodeling it in the Empire style. He walled up the first-floor windows in 1807–08 for seating room and for the King's canopied throne under its star-studded semidome.[80][44] The organ in the Ordenskapelle was brought from Kochersteinsfeld and installed in 1980, as the original had been moved to Freudental in 1814.[81]

A portion of the Bildergalerie and its frescoes

Also attached to the Ordenskapelle is the West Kavaliersbau, identical in layout and design to its eastern counter but built in 1719–20. It retains some of its original stucco and ceiling frescoes by Riccardo and Livio Retti. The Festinbau, attached to the West Kavaliersbau, was originally designed as a kitchen and built from 1729 to 1733 as a theater, complete with a proscenium that Charles Eugene used for festivities from 1770 to 1775. Since 2004, the West Kavaliersbau and the Festinbau have contained the Fashion museum (Modesmuseum).[82] The actual kitchen structure, the Küchenbau (Kitchen building), was built separately to keep odors and the threat of fire away from the palace proper.[83] Inside are seven hearths, a bakery, a butcher's shop, and several pantries, and the quarters for the servant staff in the attic and on the first floor. Most of the food prepared here was obtained locally due to the difficulty in transporting resources.[83]

The Bildergalerie (Picture gallery), the southernmost part of the west wing of the palace, spans 490 feet (150 m) to bridge the West Kavaliersbau to the New Hauptbau to the south. The gallery was built by Frisoni in 1731–32, though the only Baroque decor that remains is Pietro Scotti's ceiling fresco depicting the life of Achilles that was to adorn the ceiling of the Ahnengalerie. Friedrich von Thouret renovated the Bildergalerie in Tuscan Neoclassicism from 1803 to 1805, and it today contains a fireplace made by Antonio Isopi and a statue of Apollo by Pierre Francois Lejeune on the opposite side. Originally, this statue was carved in 1772 for the temple of Apollo in Castle Solitude's Hall of Laurels, but was then moved to Charles Eugene's library in Hohenheim Palace in 1778, and it found its way to the Bildergalerie during von Thouret's remodeling. Details on the northern and southern antechambers are lacking. The ceiling frescoes do not have an official interpretation and it is not known whether Scotti or Carlo Carlone painted them, only that the frescoes were produced in 1730.[84][85]

New Hauptbau[edit]

The New Hauptbau's corps de logis from the court of honor

The entire southern wing of Ludwigsburg Palace consists of the New Hauptbau. It was designed and constructed by Donato Frisoni on the express command of Duke Eberhard Louis, who found that the Old Hauptbau was too small to serve the needs of his court. Frisoni planned in 1725 for a four story building, but wound up building three stories from 1725 until Eberhard Louis's death, which left the building unfinished. Over a decade later in 1747, Duke Charles Eugene resumed construction in the New Hauptbau and completed its interiors in Rococo. Charles Eugene abandoned the palace in 1775, and the next royals to reside there were the first King and Queen of Württemberg, Frederick I and Charlotte Mathilde, who extensively remodeled parts of the palace in Neoclassical from 1802 to 1824 and personally resided in the New Hauptbau during the summer. After the palace ceased to be a royal residence, it was occupied by offices, and the New Hauptbau was used in 1944 and 1945 to store furnishings recovered from the recently destroyed New Palace in Stuttgart. Within the New Hauptbau is a system of secret passages crowded around two hidden courtyards, called the Dégagements, that allowed servants to travel unobserved inside the structure while on-call.[86][87]

Statuary and ceiling of the Queen's Staircase

The New Hauptbau opens with its vestibule, an oval chamber entirely decorated by Carlo Carlone and home to a statue of Duke Eberhard Louis surrounded by terms supporting a flat ceiling sporting the fresco. In the wall niches behind the columns are statues of Apollo, a woman and a sphinx, and two maenads and a satyr. A vaulted passageway decorated with two figures of Hercules leads into the Summer Salon, featuring a ceiling fresco by Diego Carlone and statues of Roman deities in niches. Next are the grand staircases on either side of the vestibule, from 1798 called the King's and the Queen's stairs, that lead up into the beletage of the New Hauptbau. The King's stairs' statuary are themed after unhappy romances while the cavettos above are adorned with stucco depictions of the seasons personified and medals bearing Eberhard Louis's initials. The Queen's staircase is a mirror of the King's, but the statuary is themed after virtues and the ribbonwork above displays Apollo, Artemis, and the four classical elements.[88]

The guardroom that forms the north entrance to the Marble Hall

Two galleries, painted with frescoes by Carlo Carlone in 1730, lead from the stairs to a guardroom also decorated by Carlone in 1730 with stucco weapon trophies and fresco, covered by von Thouret with Neoclassical ornamentation in 1815. The south door of the guardroom leads into the Marble Hall (German: Marmorsaal), the palatial dining hall once used to receive Francis I of Austria and Alexander I of Russia. Thouret began work here in 1813–14 by installing a new, curved ceiling and finished two years later with the scagliola walls. Pilasters and windows form the lower wall, decorated by stucco garlands and candelabras by Antonio Isopi and reproductions of the Medusa Rondanini, Hermes Ludovisi, and the Medici Vase above and flanking the doors. Sitting on top of this is a walkway in the attica, divided by pillars decorated by caryatids holding plates and pitchers designed by Johann Heinrich Dannecker. The ceiling fresco, by Jean Pernaux, depicts a cloudy blue sky that contains an eagle and four smaller birds that hoist the Marble Hall's chandeliers.[89][90] The roof above the Marble Hall has no visible supports, a feat achieved despite the curved ceiling, thanks to its weight being cantilevered upon the entablatures at the top of the walls of the Marble Hall.[24]

Queen Charlotte's bed

To the east of the Marble Hall is the apartment of Queen Charlotte, originally intended to house Hereditary Prince and Princess Frederick Louis and Henrietta Maria. When Charlotte joined Frederick I in residence at Ludwigsburg in 1798, the separating walls were removed to form one suite. Friedrich von Thouret only made small changes to the Queen's suite from 1802 to 1806, principally adding damask to the primary antechamber, and to the assembly and audience rooms. When she established Ludwigsburg as her residence in 1816, von Thouret began remodeling the Queen's suite in Neoclassical until 1824, sometimes incorporating prior Baroque artwork such as by Nicolas Guibal's overdoors in the assembly room. Charlotte's audience chamber contains her throne, red silk walls, and paintings of Cybele, Minerva, and personifications of Strength, Harmony, and Wisdom by Viktor Heideloff over the doors and in the lunettes of the mirrors. Next door is the bedroom, remodeled in 1824 with marbled green pilasters and an alcove containing red silk from 1760. The study, the next room to the east, is unusual for a Neoclassical interior because of its large mirrors. Finally, there is the summer study and the Queen's library, remodeled by von Thouret in 1818 with blue damask and Rococo overdoors that carry over into the library to the west. The entire apartment is furnished in the Biedermeier style by Johannes Klinckerfuss,[91][92] whose work Charlotte herself covered with embroidery.[93]

King Frederick I's bedroom

King Frederick I's apartment, to the west of Charlotte's, was to house Duke Eberhard Louis and Wilhelmine von Grävenitz and later Johanna Elisabeth of Baden-Durlach. Charles Eugene became the first to reside here in 1744 with his wife, but Charles took over her suite for his own personal residence after their separation. When Frederick I took up residence, he had Friedrich von Thouret remodel his 12-room suite from 1802 to 1811. The suite opens with the antechamber, which contains decorations dated to 1785 likely taken from Hohenheim Palace and an original ceiling fresco by Carlone of Bacchus and Venus. Next door is the audience chamber, decorated with Baroque red damask and Neoclassical borders. The room contains Frederick's throne and furniture by Isopi, featuring griffins in relief, and two ovens by Georg Matthäus Schmid. Past the conference room and its Rococo overdoors by Viktor Heideloff are the King's bedchambers. The Baroque wooden wall paneling and overdoors survived the room's 1811 remodeling. The walls and furnishing of the King's office are Neoclassical, decorated with the heads of Greek gods and cornucopias, but the ceiling fresco is a Guibal original from 1779 of Chronos and Clio.[94][95]

In 1757 Duke Charles Eugene moved into the New Hauptbau and tasked Philippe de La Guêpière with the apartment's decoration. By 1759, La Guêpière completed the entire suite except for the bedchamber, as the Duke occupied his wife Elisabeth Fredericka's suite in 1760 for his actual residence. The rest of the suite was used for social functions until they were emptied of their furnishings in the next decade. A staircase and antechamber lead into Ludovico Bossi's stuccoed gallery, the entrance of today's apartment. First are the First and Second Antechambers, clad in green damask with portraits by Antoine Pesne and paneling by Michel Fressancourt, that contain overdoors by Matthäus Günther, boiserie flooring, and furniture by Jacques-Philippe Carel and Jean-Baptiste Hédouin that Charles Eugene acquired around 1750. Next is the Assembly Room, restored in 2003, which prominently features overdoors by Adolf Friedrich Harper and trophies of musical instruments above the windows. Charles Eugene's third-floor residence begins with the Corner Room, again painted by Harper, which feeds into a cabinet room and then finally the bedchamber, completed in 1770. Bossi created the ceiling stucco in 1759–60, but it took another decade to finish, as was the case for the two further cabinets attached to the bedroom. Additional rooms on the third floor housed relatives of the Dukes and later Kings of Württemberg, but since 2004 these have been occupied by the Ceramics Museum.[96]

Grounds and gardens[edit]

A colored engraving depicting the Old Hauptbau and the Emichsburg dated to 1810

Surrounding the residential palace on three sides is the 32-hectare (3,400,000 sq ft) Blooming Baroque (Blühendes Barock) garden, which attracts 520–550,000 visitors annually.[97] Today's garden was created in 1954 and arranged in a Baroque style for Ludwigburg's 250th birthday.[98] It contains small themed gardens, most notably the Sardinian and two Japanese gardens,[99] and the Fairy-Tale Garden (Märchengarten) in the east that contains a folly and depictions of some fairy tales.[100] The garden was to be focused in the north with an Italian terraced garden and was largely completed when Duke Eberhard Louis turned his attention to the South Garden, then a collection of broderie parterres, bosquets, and an orangery, and laid out a large, symmetrical French Baroque garden.[98][101] Beginning in 1749, Duke Charles Eugene began revising the layout of the gardens by filling in the North Garden's terraces to replace it with a large broderie,[102] expanding and reorganizing the South Garden in the 1750s. Beginning in 1770, the South Garden was cleared and leased out and began falling into disrepair. Duke Friedrich II, later King Frederick I, remodeled the decayed South Garden in Neoclassical beginning in 1797, keeping the same pathways but adding a canal and fountain and dividing the South Garden into four symmetrical lawns containing an artificial hillock and Mediterranean plants held in a large vessel made by Antonio Isopi,[103] a division kept in today's South Garden.[104] Frederick I also gave the North Garden its current form in 1800,[102] expanded the garden east to form the English-style Lower East garden,[105] demolished Charles Eugene's opera house in the Upper East Garden to form a romantic medieval-themed landscape garden,[106] and created two private gardens for himself and Queen Charlotte adjacent to their New Hauptbau suites. Another addition in the Lower East Garden was the Emichsburg castle,[98] built from 1798 to 1802 and named after a knight of the Hohenstaufens and a fabled ancestor of the House of Württemberg.[107]

The Blooming Baroque garden around Ludwigsburg Palace

Frederick's son and successor, William I, abandoned Ludwigsburg for Rosenstein Palace in Stuttgart and opened the South Garden to the public in 1828.[103] The canal was filled in and an orchard planted on the southern lawns, later used to grow potatoes and vegetables. In 1947, Albert Schöchle was charged with maintaining Ludwigsburg Palace's gardens and after visiting the 1951 Bundesgartenschau in Hanover decided to restore the gardens. Schöchle convinced Baden-Württemberg's Minister of Finance Karl Frank to help fund the venture in 1952 on the condition that the city of Ludwigsburg would also assist, a stipulation to which Lord Mayor Elmar Doch and the town council agreed. Frank approved the start of work on 23 March 1953 and construction lasted into the fall. It required the moving of 100,000 cubic meters (3,531,467 cu ft) of earth by bulldozers supplied by American soldiers and the planting of tens of thousands of trees and hedges, 22,000 roses, and 400,000 individual flowers. The Blooming Baroque gardens were opened on 23 April 1954 as a special horticultural show and attracted over 500,000 visitors by the end of May, among them President Theodor Heuss. When the show closed in the fall of 1954, it had recouped all but 150,000 German marks of the investment in the restoration of the garden, which easily became a permanent landmark.[108]

The Emichsburg castle in 2006, located in the eastern gardens

On the far east side is the Fairy-Tale Garden German: Märchengarten, made up of some 40 recreations of fairy tales.[109] Opened in 1959, it was yet another addition to the palace gardens by Albert Schöchle, who was inspired by a similar garden he had seen two years earlier in Tilburg, the Netherlands.[110] The Fairy-Tale Garden was an immediate success and increased revenue by 50% that year,[111] ensuring the future of the Blooming Baroque gardens.[109]

@media all and (max-width:720px).mw-parser-output .mw-module-gallerydisplay:block!important;float:none!important.mw-parser-output .mw-module-gallery divdisplay:inherit!important;float:none!important;width:auto!important

Schloss Favorite[edit]

Schloss Favorite in the winter

Construction of Schloss Favorite began in 1704, but by 1710 Eberhard Louis, Duke of Württemberg had decided to use Ludwigsburg Palace as his main residence rather than just a hunting lodge, and charged Donato Giuseppe Frisoni with the construction of a three-winged palace in the image of the Palace of Versailles. However, the Duke still desired a hunting retreat and, inspired by a garden palace he had seen in Vienna, he tasked Frisoni with the design of a new Rococo palace to be located on a hill to the north of the main palace.[112] Frisoni largely completed Favorite within that year,[113] but was unable to complete his extensive plans for its grounds, which only resulted in the road to the main palace.[114] In 1800, the interiors of the lustschloss were remodeled by Friedrich von Thouret for King Frederick I in the Neoclassical style as the baroque interiors of the palace were by then passé and not to the King's taste.[114] Today, only one room, in the western half of the building, retains its original baroque appearance.[115] When Frederick was appointed an Elector in 1803 and made a King in 1806, he chose both times to celebrate the occasion at Schloss Favorite.[116] Favorite fell into disrepair in the 20th century but was restored true to form from 1972 to 1982. Today, Favorite is known for being the backdrop of the SWR Fernsehen talkshow Nachtcafé.[117]

Museums[edit]

On the first and third floors of the Old Hauptbau is the Baroque Gallery (German: Barockgalerie),[118] a subsidiary museum of the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart opened in 2004 that displays 120 paintings,[119][120] some of which are originals from a purchase Duke Charles Alexander made in 1736 of some 400 paintings from Gustav Adolf von Gotter. Examples of the German and Italian Baroque paintings on display include Martin van Meytens's portrait of Charles Alexander,[121] works by Johann Heinrich Schönfeld, Carl Borromäus Andreas Ruthart, Johann Heiss, and Katharina Treu as well as some works that formerly were in the collection of Cosimo III, Grand Duke of Tuscany.[122]

Ludwigsburg porcelain on display in the Ceramic museum

The Landesmuseum Württemberg maintains two subsidiary museums at Ludwigsburg Palace, the Ceramic and Fashion museums (Keramikmuseum and Modemuseum, respectively), both opened at Ludwisburg in 2004. The first of these takes up all of the third floor of the New Hauptbau but the apartment of Duke Charles Eugene, a space of 2,000 square meters (22,000 sq ft) containing over 4,500 exhibits of examples of porcelain, ceramics, faience, and pottery and the histories thereof, making it one of the largest in Europe. The museum collection contains 2,000 pieces of original Ludwigsburg porcelain and 800 pieces of Italian maiolica, purchased by Charles Eugene from dealers in Augsburg and Nuremberg. In totality, the museum collection includes porcelain from the manufactories at Meissen, Berlin, Sèvres, and Vienna, and 20th century Art Nouveau pieces purchased from six countries since 1950.[123][124][125] The Fashion museum, housed in the Festinbau and West Kavaliersbau,[126] displays about 700 various pieces of clothing and accessories from the 1750s to the 1960s, including articles of clothing by Charles Frederick Worth, Paul Poiret, Christian Dior, and Issey Miyake.[127][128]

On the ground floor of the New Hauptbau is the lapidarium, housing original Baroque statuary by Andreas Philipp Quittainer, Carlo and Giorgio Feretti, Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Beyer and Pierre François Lejeune adversely affected by over two centuries of erosion.[129] The second floor of the New Hauptbau hosts the Princess Olga Cabinet Exhibition, exploring the life and times of the royal family of Württemberg in the 20th century though historical photographs taken inside the palace. In Charles Eugene's apartment, on the third floor of the New Hauptbau, is the Princess Olga Cabinet, displaying pictures taken during the residence of Princess Olga and her husband in Charles Eugene's apartment from 1901 to 1932.[130]

For children over four years of age, there is an interactive museum called the Kinderreich (Children's Kingdom), which aims to teach children about life in the court of the Duke of Württemberg via hands-on methods that include the wearing of period dress. Children are led through the dressing room, then to a mock courtroom that hosts several stations that recreate aspects of court life at Ludwigsburg.[131][132] The Children's Stage is yet another facet of the Kinderreich where children learn about Baroque stage performance. Preserved in the Palace Theater are about 140 original set pieces and props from the 18th and 19th centuries that were discovered during restoration work on the Theater, such as oil lamps used for stage lighting. These items were extensively restored to their original condition from 1987 until 1995, and since 1995 one of the original stage pieces has been used for the Children's Stage (German: Junge Bühne).[133][11]

See also[edit]

- List of Baroque residences

- New Palace (Stuttgart)

- Würzburg Residence

- Palace of Versailles

Notes[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

^ Samantha Owens writes in Music at German Courts, 1715–1760 that settlers in Ludwigsburg had 20 years without taxation,[9] while the official websites for the city of Ludwigsburg and that of its museum of history state 15 years.[6]

^ Both chapels were intended to be Lutheran and separated according to court function, but the Schlosskapelle would be Roman Catholic from 1737 to 1798 because of the reigns of Catholics Karl Alexander and Charles Eugene,[4] while the approximately 600 Catholics in Ludwigsburg, mostly Italians, were forbidden by law from worshiping in their rite until 1806. Since 1829, the Schlosskapelle has been a Catholic institution and is today only used for festive functions.[21] The Ordenskapelle has been Protestant since the reign of Duke Charles Eugene.[22]

Citations[edit]

^ Dorling 2001, p. 292.

^ Region Stuttgart: Ludwigsburg Palace.

^ ab Wenger 2004, p. 3.

^ abcdefghijklmnopqr Süddeutscher Barock: Ludwigsburg.

^ Owens 2011, pp. 166–167.

^ abcdef Ludwigsburg Museum.

^ Kaufmann 1995, p. 320.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 3, 5.

^ ab Owens 2011, p. 175.

^ Charles & Carl 2010, p. 141.

^ abcd Ludwigsburg Palace: Das Schlosstheater.

^ ab Süddeutscher Barock: Philipp Joseph Jenisch.

^ ab Wenger 2004, pp. 3–4.

^ abc Ludwigsburg Palace: Die Gebäude.

^ Wilson 1995, p. 128.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 4, 12, 35.

^ Süddeutscher Barock: Johann Friedrich Nette.

^ ab Süddeutscher Barock: Donato Giuseppe Frisoni.

^ abc Ludwigsburg Palace: Donato Giuseppe Frisoni.

^ Wenger 2004, p. 4.

^ ab Ludwigsburg Palace: Die Schlosskapelle.

^ abc Wenger 2004, p. 7.

^ ab Wenger 2004, p. 5.

^ abcd Ludwigsburg Palace: Die Dächer.

^ Wenger 2004, p. 6.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 6–7.

^ ab Ludwigsburg Palace: Der Neue Hauptbau.

^ Wilson 1995, p. 36.

^ ab Wilson 1995, p. 165.

^ Wilson 1995, p. 184.

^ ab Stuttgarter Zeitung, 28 November 2014.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 7–8.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Das Appartement von Herzog Carl Eugene.

^ abc Wenger 2004, p. 8.

^ ab Curzon 2016, p. 70.

^ ab Wenger 2004, p. 9.

^ Hazlitt 1830, p. 143.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Friedrich I von Württemberg.

^ ab Wenger 2004, pp. 9–10.

^ Curzon 2016, pp. 70–1.

^ ab Wenger 2004, pp. 10–11.

^ Panton 2011, p. 103.

^ abcde Wenger 2004, p. 11.

^ abcd Ludwigsburg Palace: Ordensbau und Ordenskapelle.

^ abc Ludwigsburg Festival: Chronicle.

^ Weingartner 2011, p. 49.

^ Südwest Presse, 10 August 2016.

^ Rosi's Sammlerstube: Schloss Ludwigsburg.

^ StampWorld: Ludwigsburg Castle.

^ US Army, 27 October 2011.

^ BaWü Ministry of Finance: Schlösserreise nach Ludwigsburg und Stuttgart.

^ Stuttgarter Nachrichten, 22 April 2016.

^ Stuttgarter Nachrichten, 6 December 2017.

^ Ministry of Finance: Sondermarken Februar 2017.

^ ab Stuttgarter Nachrichten, 17 November 2017.

^ ab BaWü Ministry of Finance: Finanzministerin besucht Residenzschloss Ludwigsburg.

^ SWP.de, 25 May 2018.

^ Stuttgarter Nachrichten, 2 February 2017.

^ ab Porcelain Marks: Ludwigsburg.

^ ab Ludwigsburg Palace: Die Porzellanmanufaktur.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Stilgeschichte.

^ Kaufmann 1995, p. 321–22.

^ ab Ludwigsburg Palace: Der Alte Hauptbau.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 12–13, 16–17, 18.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 23–24.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 24–28.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Der Jagdpavillon.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 28–30.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Der Spielpavillon.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 35–41.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 43–45.

^ Orgelsammlung Gabriel Isenberg: Ludwigsburg Schlosskirche.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 48–49, 91, 92–93.

^ BaWü Ministry of Tourism: Ludwigsburg Residential Palace.

^ SWP.de, 15 January 2018.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 84–87.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Die Ahnengalerie.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 31–34.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Meilensteine.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 46–48.

^ Orgelsammlung Gabriel Isenberg: Ludwigsburg Ordenskapelle.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 48, 49, 90.

^ ab Ludwigsburg Palace: Der Küchenbau.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 84, 88–90.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Die Bildergalerie.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 6, 8, 11, 50, 65–66.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Die Dienerschaftszimmer.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 51–53.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 54–56.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Der Marmorsaal.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 66–74.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Das Appartement der Königin.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Charlotte Mathilde von Württemberg.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 56–64.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Das Appartement des Königs.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 75–83.

^ Blooming Baroque: Facts and Figures.

^ abc Ludwigsburg Palace: Der Garten.

^ Blooming Baroque: A Tour in Pictures.

^ Blooming Baroque: Fairy-Tale Garden.

^ Blooming Baroque: South Garden (Südgarten).

^ ab Blooming Baroque: North Garden (Nordgarten).

^ ab Blooming Baroque: History of the Ludwigsburg Palace Garden.

^ Blooming Baroque: South Garden.

^ Blooming Baroque: Lower East Garden (Unterer Ostgarten).

^ Blooming Baroque: Upper East Garden (Obere Ostgarten).

^ Blooming Baroque: Emichsburg castle.

^ Blooming Baroque: Albert Schöchle's idea.

^ ab Blooming Baroque: The Fairy-Tale Garden.

^ Blooming Baroque: Creation of the Fairy-Tale Garden.

^ Blooming Baroque: Another success for Albert Schöchle.

^ Schloss Favorite: Das Schloss und der Garten.

^ Süddeutscher Barock: Favorite Ludwigsburg.

^ ab Schloss Favorite: Das Gebäude.

^ Schloss Favorite: Die westlichen Zimmer.

^ Schloss Favorite: Meilensteine.

^ Schloss Favorite: Home.

^ Wenger 2004, p. Foldout map.

^ Ludwigsburg: Barockgalerie.

^ Landeskunde Online: Barockgalerie in Schloss, Intro 1.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Die Barockgalerie.

^ Landeskunde Online: Barockgalerie in Schloss, Intro 2.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Das Keramikmuseum.

^ Landesmuseum Württemberg: Keramikmuseum.

^ Ludwigsburg: Keramikmuseum.

^ Wenger 2004, pp. 49, 91, Foldout map.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Das Modemuseum.

^ Landesmuseum Württemberg: Modemuseum.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Das Lapidarium.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Die Kabinettausstellung Prinzessin Olga.

^ Ludwigsburg: Kinderreich Schloss Ludwigsburg.

^ Ludwigsburg Palace: Das Kinderreich.

^ Ludwigsburg: Junge Bühne.

References[edit]

.mw-parser-output .refbeginfont-size:90%;margin-bottom:0.5em.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ullist-style-type:none;margin-left:0.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>ul>li,.mw-parser-output .refbegin-hanging-indents>dl>ddmargin-left:0;padding-left:3.2em;text-indent:-3.2em;list-style:none.mw-parser-output .refbegin-100font-size:100%

Charles, Victoria; Carl, Klaus H. (2010). Rococo. Baseline Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84484-740-2.

Curzon, Catherine (31 August 2016). Life in the Georgian Court. Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-4554-1.

Dorling Kindersley (6 August 2001). Eyewitness Travel Guide to Germany. Eyewitness Travel Guide. Dorling Kindersley Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7894-6646-4.

Hazlitt, William (1830). The Life of Napoleon Buonaparte. III. Hunt and Clarke.

Kaufmann, Thomas DaCosta (1995). Court, Cloister, and City: The Art and Culture of Central Europe, 1450–1800. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-42729-4.

Owens, Samantha; Reul, Barbara M.; Stockigt, Janice B., eds. (2011). "The Court of Württemberg-Stuttgart". Music at German Courts, 1715–1760: Changing Artistic Priorities. Forward by Michael Talbot. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-598-1.

Panton, James (24 February 2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7497-8.

Weingartner, James J. (2011). Americans, Germans and War Crimes Justice: Law, Memory and "the Good War". ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-313-38192-8.

Wenger, Michael (2004). Ludwigsburg Palace: The Interior. State Agency of Palaces and Gardens. ISBN 978-3-422-03100-5.

Wilson, Peter H. (23 March 1995). War, State, and Society in Württemberg, 1677–1793. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-48331-5.

- News sources

Jones, Capt. Gregory (27 October 2011). "21st TSC Soldiers invited to Minister President's reception". 21st TSC Public Affairs. US Army. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

Höhn, Tim (28 November 2014). "Sex, Stars und große Oper". Stuttgarter Zeitung (in German). Retrieved 10 March 2018.

Binkowski, Rafael (22 April 2016). "Lego-Ausstellung in historischer Kulisse". Stuttgarter Nachrichten. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

Szczegulski, Gabriele (10 August 2016). "KSK Music Open in Ludwigsburg werden zur Marke". Bietigherim Zeitung (in German). Südwest Presse. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

Laibacher, Ludwig (2 February 2017). "Als die Fürsten begannen, Emotionen zu zeigen". Stuttgarter Nachrichten. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

Binkowski, Rafael (17 November 2017). "Rokoko-Meisterwerk ist eine Million Wert". Stuttgarter Nachrichten. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

"Ufos, Märchen und Laternen". Stuttgarter Nachrichten. 6 December 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

Szczegulski, Gabrielle (15 January 2018). "Italiener bringt Glanz nach Ludwigsburg". Bietigheimer Zeitung. Retrieved 30 May 2018.

"Der textile Prunk im Ludwigsburger Schloss". swp.de (in German). 25 May 2018. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

Online references[edit]

"Sondermarken Februar 2017". bundesfinanzministerium.de (in German). Federal Ministry of Finance. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

"2004 300 Jahre Schloss Ludwigsburg". briefmarken-versand-welt.de (in German). Rosi's Sammlerstube. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

"The 300th Anniversary of Ludwigsburg Castle". stampworld.com. StampWorld. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

Marshall, Christopher S. "Ludwigsburg". porcelainmarksandmore.com. Porcelain Marks and More. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

"Ludwigsburg palace". stuttgart-tourist.de/en. Region Stuttgart. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Schloss Ludwigsburg (Schlosskirche)". orgelsammlung.de (in German). Orgelsammlung Gabriel Isenberg. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

"Schloss Ludwigsburg (Ordenskapelle)". orgelsammlung.de (in German). Orgelsammlung Gabriel Isenberg. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

Bühler, Dr. Christoph. "Barockgalerie in Schloss Ludwigsburg". zum.de (in German). Landeskunde Online. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

Bühler, Christoph. "Barockgalerie in Schloss Ludwigsburg". zum.de (in German). Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Keramikmuseum". landesmuseum-stuttgart.de (in German). Landesmuseum Württemberg. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Modemuseum". landesmuseum-stuttgart.de (in German). Landesmuseum Württemberg. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- Baden-Württemberg State Agency of Palaces and Gardens (in German)

"Stilgeschichte". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

"Meilensteine". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 7 June 2018.

"Die Gebäude". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Der Alte Hauptbau". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Der Jagdpavillon". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Der Spielpavillon". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Ordensbau und Ordenskapelle". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Der Neue Hauptbau". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Der Marmorsaal". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

"Das Appartement des Königs". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

"Das Appartement der Königin". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

"Das Appartement von Herzog Carl Eugene". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

"Die Schlosskapelle". Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

"Die Bildergalerie". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

"Die Ahnengalerie". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

"Das Schlosstheater". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Der Küchenbau". schloss-ludwigsburg.dee. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

"Der Garten". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"Die Dächer". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Die Dienerschaftszimmer". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Friedrich I. von Württemberg". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

"Charlotte Mathilde von Württemberg". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

"Donato Giuseppe Frisoni". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Die Porzellanmanufaktur". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 9 December 2017.

"Die Barockgalerie". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Das Keramikmuseum". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Das Modemuseum". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Das Lapidarium". schloss-ludwigsburg. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Die Kabinettausstellung Prinzessin Olga". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

"Das Kinderreich". schloss-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Das Schloss und der Garten". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Meilensteine". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Das Gebäude". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Home". www.schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de/en. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Die westlichen Zimmer". schloss-favorite-ludwigsburg.de. Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- German Federal and State governments

"Schlösserreise nach Ludwigsburg und Stuttgart". fm.baden-wuerttemberg.de (in German). Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Finance. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

"Finanzministerin besucht Residenzschloss Ludwigsburg". fm.baden-wuerttemberg.de (in German). Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Finance. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

"Ludwigsburg Residential Palace". tourism-bw.com. Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Tourism. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- City of Ludwigsburg

"Chronicle". schlessfestspiele.de/en. Ludwigsburg Festival. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Ideal city". ludwigsburgmuseum.de. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Barockgalerie". ludwigsburg.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

"Keramikmuseum". ludwigsburg.de (in German). City of Ludigsburg. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

"Kinderreich Schloss Ludwigsburg". ludwigsburg.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Junge Bühne". ludwigsburg.de (in German). City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Facts and Figures". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"A Tour in Pictures". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"Fairy-Tale Garden". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"South Garden (Südgarten)". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"North Garden (Nordgarten)". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"History of the Ludwigsburg Palace Garden". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"South Garden". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

"Lower East Garden (Unterer Ostgarten)". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"Upper East Garden (Obere Ostgarten)". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"Emichsburg castle". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

"Albert Schöchle's idea of Blühendes Barock (Baroque in Bloom)". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

"The Fairy-Tale Garden at Baroque in Bloom". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

"Creation of the Fairy-Tale Garden". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

"Another success for Albert Schöchle". Blühendes Barock. City of Ludwigsburg. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Süddeutscher Barock (in German)

Bieri, Pius. "Ludwigsburg". sueddeutscher-barock.ch. Süddeutscher Barock. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

Bieri, Pius (2011). "Favorite Ludwigsburg". sueddeutscher-barock.ch. Süddeutscher Barock. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

Bieri, Pius. "Philipp Joseph Jenisch". sueddeutscher-barock.ch. Süddeutscher Barock. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

Bieri, Pius. "Johann Friedrich Nette". sueddeutscher-barock.ch. Süddeutscher Barock. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

"Donato Giuseppe Frisoni". sueddeutscher-barock.ch. Süddeutscher Barock. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Residenzschloss Ludwigsburg. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Ludwigsburg Palace. |

Official website for Ludwigsburg Palace (in English)

Official website for Schloss Favorite (in English)

Categories:

- Castles in Ludwigsburg

- Buildings and structures in Ludwigsburg

- Art museums and galleries in Germany

- Baroque architecture in Baden-Württemberg

- Baroque palaces

- Buildings and structures in Ludwigsburg (district)

- Burial sites of the House of Beauharnais

- Burial sites of the House of Urach

- Burial sites of the House of Württemberg

- Castles in Baden-Württemberg

- Ceramics museums

- Decorative arts museums in Germany

- Fashion museums

- Gardens in Baden-Württemberg

- Historic house museums in Baden-Württemberg

- Houses completed in 1733

- Ludwigsburg

- Museums in Baden-Württemberg

- Palaces in Baden-Württemberg

- Royal residences in Baden-Württemberg

(window.RLQ=window.RLQ||).push(function()mw.config.set("wgPageParseReport":"limitreport":"cputime":"1.940","walltime":"2.225","ppvisitednodes":"value":11460,"limit":1000000,"ppgeneratednodes":"value":0,"limit":1500000,"postexpandincludesize":"value":321257,"limit":2097152,"templateargumentsize":"value":12530,"limit":2097152,"expansiondepth":"value":11,"limit":40,"expensivefunctioncount":"value":5,"limit":500,"unstrip-depth":"value":1,"limit":20,"unstrip-size":"value":88611,"limit":5000000,"entityaccesscount":"value":1,"limit":400,"timingprofile":["100.00% 1572.131 1 -total"," 24.27% 381.594 74 Template:Cite_web"," 20.58% 323.602 204 Template:Sfn"," 10.06% 158.212 8 Template:Navbox"," 8.20% 128.841 1 Template:Infobox_building"," 7.55% 118.638 7 Template:Lang-de"," 7.23% 113.610 1 Template:Infobox"," 6.82% 107.290 1 Template:Fortifications"," 6.22% 97.781 2 Template:Reflist"," 5.76% 90.507 10 Template:Cite_book"],"scribunto":"limitreport-timeusage":"value":"1.023","limit":"10.000","limitreport-memusage":"value":26613416,"limit":52428800,"cachereport":"origin":"mw1241","timestamp":"20180830142812","ttl":1900800,"transientcontent":false);mw.config.set("wgBackendResponseTime":80,"wgHostname":"mw1250"););

Clash Royale CLAN TAG

Clash Royale CLAN TAG